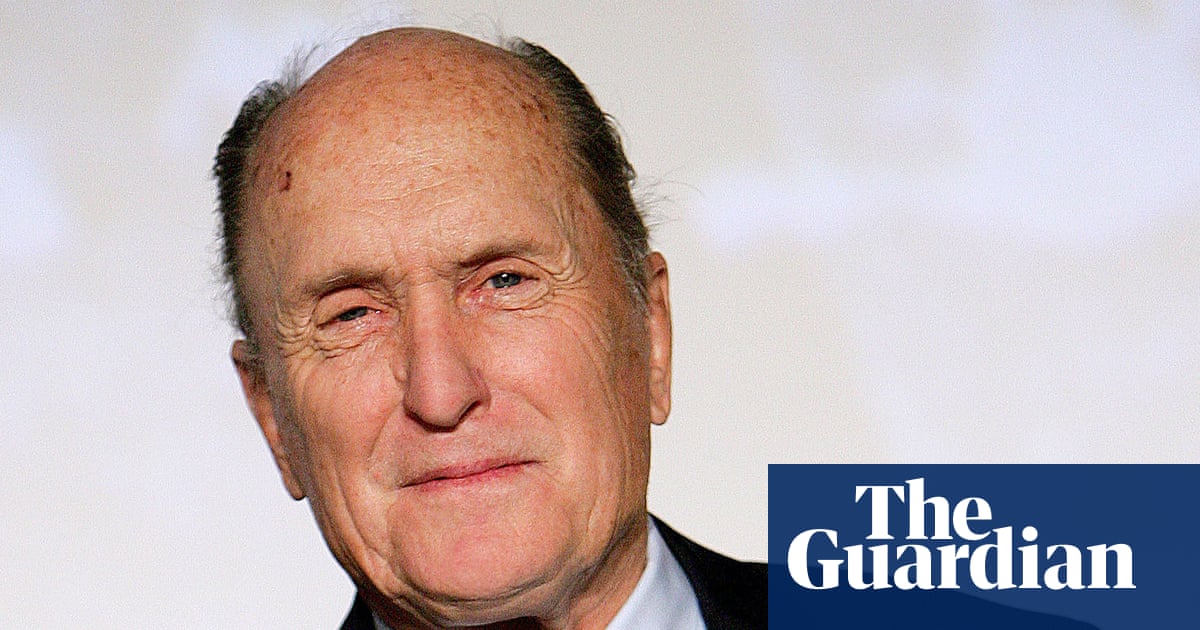

Robert Duvall was a foghorn-voiced bull of pure American virility, and he put energy and heart into the movies for more than 60 years. Just to see him on screen was enough to make me smile. That handsome face and head gave him the look of a Roman emperor from Waxahachie, Texas or a three-star general playing the country music circuit. Duvall was famously bald (the rare roles needing hairpieces always looked artificial on him) and so he looked the same age almost all his acting life: forever in his vigorous fortysomething prime – though often playing figures complicated with tenderness and woundedness.

Duvall had a long, rich career, starting out with notable roles in To Kill a Mockingbird, M*A*S*H, The Conversation and Network, but it was destiny to be chiefly known for two sensational and very different roles given to him by Francis Ford Coppola at either end of the 1970s. One was Tom Hagen, the quiet, self-effacing consigliere to the Corleone crime family in The Godfather (1972), with a complex relationship both with the Don himself, played by Marlon Brando, and his youngest son and heir, the coldly imperious Michael, played by Al Pacino. And the second was his extraordinary turn as the surf-crazed Wagner enthusiast Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore in Apocalypse Now (1979), who with his “Air Mobile” division of helicopters leads a gigantic attack on a Vietnamese village in broad daylight, with speakers blaring The Ride of the Valkyries – in theory to airlift Captain Willard, played by Martin Sheen, and his boatful of men into the river’s strategic entry point. But all too clearly, it’s because he just wants an excuse for a whooping and hollering cavalry attack.

On the other hand, Duvall’s Hagen in The Godfather is one of his subtlest and most misunderstood performances. He is calm and reserved, an administrator and COO figure of the Corleone corporation; Hagen has to endure insults from Vito’s raging hothead son Sonny (James Caan) that what the family needs is a “wartime” consigliere, not this milksop. When Michael later crisply excludes him from the inner circle, relegating him to the status of his Vegas lawyer, Duvall shows how deeply hurt Hagen is.

Yet it is mild Hagen who is responsible for the most macabre and legendary act of violence in the whole Godfather canon: the horse’s head in the bed. Vito had tasked him with flying out to Los Angeles to meet a certain movie producer who was refusing to cast Johnny Fontane – the Sinatra-esque singer who is Vito’s godson. The producer diplomatically entertains Hagen to dinner at his lavish Hollywood home, having shown him the racehorse in his stables: his pride and joy. But he still refuses to have anything to do with Fontane. Hagen leaves, apparently accepting the decision. The following morning we see the horrifying result. And we realise that in the intervening eight hours, Hagen has mobilised local muscle to break noiselessly into the producer’s property – with Hagen naturally leading the way as someone who knows the layout – get into the stables, drug the horse, saw its head off, sneak into the producer’s bedroom, place the head between the sheets and silently leave. An extraordinary act of psychopathic ingenuity and daring. Back in New York, Hagen is solicitously asked by the Don if he is tired and Hagen just shrugs that he “slept on the plane”. Later, when Tessio is about to be killed for conspiring against Michael, it is to Hagen that he whines: “Tell Mike it was only business. I always liked him” and even asks for Hagen’s help. Duvall’s face is a mask of contemptuous amusement.

There is something of the same steel in the outrageous Kilgore in Apocalypse Now, who booms, shirtless, while squatting athletically down on his haunches to address the men: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning!” – adding with a mysterious hint of regret: “Some day this war’s gonna end.” He has nothing but contempt for the enemy because they don’t understand his love of surfing: “Charlie don’t surf!” And he brushes off a subordinate’s incomprehension: “What do you know about surfing, Major? You’re from goddamned New Jersey!” Duvall delivers these mysterious arias of craziness with absolute conviction.

That same year, he had a comparably intimidating role The Great Santini (1979), in which he plays a US marine corps officer, “Bull” Meacham, who is in the habit of playing one-on-one basketball games with his teenage son Ben in the front driveway, and simply cannot accept it when Ben finally beats him. The father bullies and humiliates the son in an unwatchable scene.

Duvall got his best actor Oscar for a movie that tapped much more into his wistful loneliness: Bruce Beresford’s Tender Mercies in 1983, in which he played Mac Sledge, a country singer who has lost wife, daughter and career to drink. Mac wakes up broke and hungover in a Texas motel room, persuades the manageress (the widow of a fallen Vietnam veteran) to let him stay and winds up marrying her. It’s a lovely, gentle performance from Duvall, who incidentally has a great singing voice and performs two songs of his own composition: Fool’s Waltz and I’ve Decided to Leave Here Forever. The whole movie is itself like a country song, melancholy and a little mawkish, with Duvall at its centre.

But my favourite of Duvall’s films is the one that resembles Tender Mercies more than a little, in its story of mysterious spiritual redemption in the American heartland. It was Duvall’s own passion project: The Apostle (1997), in which he was writer, producer, director and star. He is the low-church preacher Euliss F “EF” Dewey, who has lost his wife and children to the booze. Drunk, he shows up at his kid’s baseball match and fatally hits his estranged wife’s new boyfriend with a bat; he goes on the run, winding up in Louisiana where, through sheer force of will and preaching eloquence, he sets up a new church and becomes a much-loved figure in the town.

Duvall created a lovely, almost Hardyesque story with The Apostle, a kind of Mayor of Casterbridge for the deep south. It was entered for the Un Certain Regard section in Cannes; I think it should have been in competition, and could have carried off the Palme. EF is not supposed to be an ironic or sinister figure in any way, despite his crime, and his lack of obvious repentance. It is genuinely sad when his courtship of a local woman (Miranda Richardson) doesn’t work out, and gripping when he confronts a local bigot (Billy Bob Thornton). And it is very moving when he conducts his final service in his little church as the police gather outside, having agreed to let him finish. This is a glorious performance from Duvall, with something playful in the flights of preaching fancy, especially when holding forth on the radio, in a sporting stance at the microphone, one foot forward, the other back, he bellows genially about “holy ghost power!”

Duvall always had power, and a little of that power has left the movies today.

4 hours ago

4

4 hours ago

4