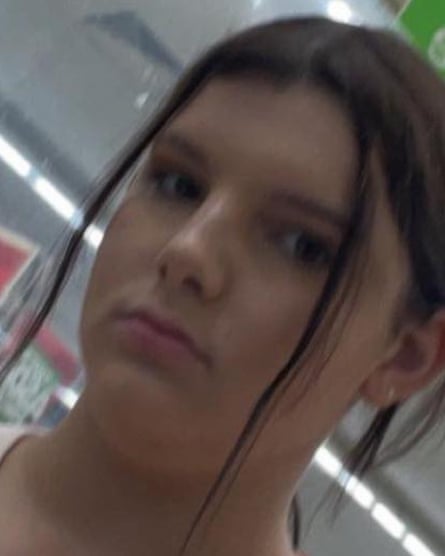

The mother of a girl who was struck by a vehicle and killed after she left a police car on a motorway says the untimely death of her daughter came after years of frustration and disappointment with authorities over the teenager’s care.

Tamzin Hall, 17, had been arrested and was being taken into custody when she left the police vehicle in which she was travelling on the M5 northbound between Taunton and Bridgwater in Somerset on 11 November 2024.

Tamzin, who had been diagnosed with autism and was living in a children’s home in Somerset at the time of her death, jumped over the motorway barrier and was struck by a car on the southbound carriageway between junctions 24 and 25.

Tamzin’s mother, Amy Hall, a former adult social care worker from Wellington, Somerset, says she has been left with many unanswered questions over her daughter’s death, criticising the police, social care and health trusts for how Tamzin had been cared for and treated since her early teens.

Hall was concerned by coverage of Tamzin’s death, which she believes has portrayed her daughter unfairly and inaccurately, arguing that Tamzin should always have been approached as a person with severe mental health difficulties rather than someone with social or behavioural problems.

“She needed specialised help, and that’s what she never got, and that’s what I was trying to fight all the way through, and no one would ever listen to me,” Hall says.

On the night she died, Tamzin was close to her 18th birthday and had become deeply distressed about the prospect of being legally treated as an adult, fearful she would be abandoned and moved to another home far from her family. She consumed alcohol and became increasingly agitated.

The police were called, something Hall says some of the staff at the children’s home were too quick to do. She would have benefited from a member of staff with the training and qualifications to deal with a young woman in distress, rather than reverting to calling the police, Hall says.

Two female police officers arrived and placed Tamzin in the police car to take her to Bridgwater police station.

Tamzin had been at the home for about a year at the time of her death. Hall says she was extremely vulnerable and wants to know what, if any, risk assessments were taken by the police before she was arrested.

Hall has only been able to get answers to what happened next through her conversations with Avon and Somerset police and the IOPC, which is investigating what happened. Both officers have been served with misconduct notices for a potential breach of their duties and responsibilities by the IOPC. An inquest before a jury is scheduled to take place in November.

First, Hall questions why Tamzin was placed in a car, rather than a secure van, which she feels would have been more appropriate. One of the officers sat in the back with Tamzin, while the front passenger seat remained empty, she says.

The IOPC has publicly confirmed that Tamzin removed her handcuffs, but has not explained to Hall how that was possible. She understands that Tamzin was then able to climb from the rear to the front of the vehicle and open the door without being stopped.

There is no camera footage of the journey, Hall understands, including body-worn cameras.

“Cameras should be worn as soon as a child is arrested,” Hall says.

She says when the car came to a stop and Tamzin left the vehicle, one of the officers exited, but after hearing a collision on the other side of the motorway, returned to the car. The officers then left the area, driving northbound up the motorway to turn back south.

“Why wasn’t she in a van? How did she remove the handcuffs and why? Why didn’t they pin Tamzin down? Why didn’t they hit the panic button on their cameras? Why did they abandon the scene?

“I’ve completely lost faith in the police,” she says.

A spokesperson for Avon and Somerset police said: “Our thoughts remain with Tamzin Hall’s family. It’s clear how loved she was and how much she is dearly missed by those who knew her.

“We are committed to being open and transparent about what happened and we have said from the outset that we will do whatever we can to assist the IOPC’s inquiries.

“That investigation has not yet concluded and therefore it would not be appropriate for us to pre-judge or speculate on what the IOPC’s findings will be.

“We are also mindful of the welfare of our officers who were at the scene at the time of Tamzin’s death. We are ensuring their welfare is considered and they receive the necessary support during the course of this investigation.”

Tamzin grew up in a normal family, Hall says. She was a “lovely, quiet child” who was sporty, caring and helpful. She had five siblings, now age 21 to two. Her older brother is studying law at university.

When she was eight years old, she lost her dad to cancer. “Tamzin was extremely close to her dad, so that was quite a traumatic loss,” Hall says.

after newsletter promotion

It was in her early teens at Court Fields school in Wellington that she started to display difficult behaviour and appeared to be struggling mentally. She would frequently leave the house unannounced and “go out wandering” on her own, Hall says.

“A lot of people had suspicions – looking at the behaviour going on – that she had autism,” she says, but they were unable to get an immediate diagnosis.

Tamzin soon started self-harming and was hospitalised. “It was really difficult trying to go to work and look after Tamsin because she was quite unsafe,” Hall says, explaining she later had to leave her role in adult social care due to the pressures of caring for Tamzin and her siblings.

At school she was separated from most of the other children in a behavioural hub. During the Covid pandemic her behaviour deteriorated and she was referred to child and adolescent mental health services (Camhs).

While staff at Camhs talked about Tamzin possibly displaying autism and ADHD, the assessment delays were so long that nothing could be done immediately, Hall says. She had irregular appointments and was occasionally provided with medication for anxiety and depression, as well as a short spell of cognitive behavioural therapy, none of which had any significant impact.

At this stage, Hall was already of the view that Tamzin needed long-term supervised mental healthcare and to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act. But this did not happen, and never did.

“She had trauma from losing her dad, she was carrying autism and masking it for a long time,” Hall says.

After Tamzin took an overdose of paracetamol, Hall says she pushed healthcare services to detain her in hospital but was told Tamzin had yet to reach the threshold.

At about the age of 15, Tamzin was removed from her mother’s home and put in a succession of unregulated placements – accommodation for children in care which are not registered or inspected by Ofsted.

It was initially supposed to be temporary but Hall says the placements were “extended and extended” each time there was an incident involving Tamzin. Hall estimates that Tamzin went to about 25 different placements over a period of about one year.

“What she needed was professional mental health help,” she says. “It was completely the wrong environment.”

Finally, Tamzin was moved to a supported living children’s home run by Homes2Inspire. Hall was able to continue to see Tamzin on most days, either at the children’s home or in her own home in Wellington.

While she was impressed by the work of some of the staff, she ultimately felt this again was not the right environment for Tamzin.

“If she was put into an environment where you’ve got doctors and professionals assessing her medication every day, whether it be for a week, two weeks, two months, whatever needed to be done, it should have been done from day one, rather than putting her into care.”

The Homes2Inspire staff varied from those with “great relationships” with Tamzin who went “above and beyond” to others who appeared to want an “easy shift” and rarely even spoke to Tamzin, Hall says.

“Tamzin always wanted to be at home, but she always used to say ‘Mum, I know why I can’t be at home because no one’s helping me. I’ve never got better. No one helps me. Why do I do these things? No one ever helps me.’”

A spokesperson on behalf of Somerset council, Somerset NHS foundation trust and Homes2Inspire said: “Our thoughts remain with Amy, Tamzin’s family, and all those affected by this devastating incident. We are supporting the Independent Office of Police Complaints investigation into the circumstances leading up to Tamzin’s tragic death and do not want to prejudice this process by commenting further at this time.”

3 months ago

120

3 months ago

120