Britain’s puddings are under threat. According to research from English Heritage, only 2% of British households eat a daily homemade dessert, while a third never bake, boil or steam one at all.

“Sweet puddings are closely intertwined with British history and it would be a huge shame for them to die out,” said the charity’s senior curator of history, Dr Andrew Hann. But he went on to suggest that, at the current rate of decline, the British pudding will be extinct in 50 years.

Leaving aside complex questions about what does and doesn’t constitute a British pudding – we know an apple crumble is one, and a Calippo isn’t – we must ask ourselves why we’ve stopped producing old-fashioned cooked desserts. Do we lack the time, or the skill – or both? Have tastes changed? Have certain classic puddings simply faded from Britain’s collective memory?

I can’t answer that last one – I’m American. I’ve been exposed to many British puddings over the years, but I have no history with them, or nostalgia for them. To remedy this, I tried cooking 10 of Britain’s endangered puddings, in an attempt to find out which, if any, are worthy of a rescue effort, and which may deserve their approaching extinction.

Jam roly-poly

I’ve never eaten a jam roly-poly, AKA shirt-sleeve pudding, AKA dead man’s arm. My adult British children reckon they have had it for school dinners, but they were as surprised as I was by the recipe, especially the generous amount of beef suet. Suet, the fat around the kidneys of the animal, is commonly available in a fairly inoffensive, pelleted form. There is a vegetable version, but I stuck with the original.

I watched chef Aaron Middleton’s video tutorial, because I figured there would be some technique to master, but the dough itself is basic: self-raising flour, butter, suet, sugar, milk. Once it comes together, you flatten it into a large rectangle, slather the whole thing in raspberry jam, roll it up and pinch the ends.

This assembly is then wrapped in a parcel of greaseproof paper and foil, and steamed in the oven, with a roasting tin full of boiling water sitting on the rack below.

The most generous thing I could say about my first jam roly-poly is that it let me down: it didn’t rise; it didn’t form a crust; it didn’t, to be honest, come out of the oven looking materially different from when I put it in. If I were being less generous, I would also add that it was disgusting – claggy, sickly sweet and still raw in places. Something went wrong, and I’m not sure what. I forced a slice on my middle son and dared him to be complimentary.

“You can really taste the suet,” he said.

Star rating (1 being the least palatable/hardest to make, and 5 the nicest/easiest): taste: 1; ease: 1

Sussex pond pudding

I followed Mary Berry’s recipe for this timeless British pudding that I’ve never heard of; you have to wonder if the name isn’t a big part of the problem. Sussex pond pudding is made with apples, muscovado sugar and, yes, more suet. It also has a whole lemon at its heart, which I guess you’re supposed to cut around when you serve it. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

It employs a similar dough to the one for the jam roly-poly that failed me so badly, though perhaps this one is a little drier. The apples are peeled, cored, diced into cubes and mixed with cold butter and sugar. You also need a pudding basin of about 1.5 litres capacity, or around 20cm diameter across the top.

The basin is thoroughly buttered, the dough rolled out into a 30cm circle. Slice out one quarter of it – from noon to 3pm, say – and reserve. The remainder should fit snugly into the contours of your pudding bowl. Spoon a bit of the apple, butter and sugar mixture into the bottom of the pastry lining. Pierce the lemon all over with a fork or cocktail stick and sit it upright in the mixture. Surround that with more apples, and then turn your reserved dough into a circular lid.

I had to watch a video of a guy sealing and tying his pudding bowl for steaming several times – it’s complicated – but you fashion a covering from a layer of greaseproof paper and one of foil, with a pleat down the middle for expansion. Then, you tie string tightly round the edge (pudding basins have a pronounced lip for this purpose), create a handle from more string, and trim off the excess foil. The resulting parcel is pretty impressive – if only one was allowed to stop there.

This package goes into a big pan with a tight-fitting lid, with boiling water poured halfway up the sides of the bowl. Simmer with the lid on for – get this – three-and-a-half hours, topping up the water as needed.

As soon as it’s cool enough, invert over a plate; you should end up with a crusty dome surrounding an apple pie filling. And a lemon.

I used to think I understood what the word stodgy meant in a culinary context, but the Sussex pond pudding has reset my frame of reference. This is, by some measure, the heaviest dessert I’ve ever made, and while it’s not terrible, I can’t think of anything to recommend it over a hundred other apple-based foodstuffs, including an apple.

Taste: 2; ease: 2

Bread and butter pudding

Besides suet, the other big ingredient you’ll find in endangered British puddings is old bread – the older the better. Many pudding recipes even offer tips for ageing bread which is insufficiently past it.

I’ve tasted – and, with certain reservations, enjoyed – bread and butter pudding in the past, but I’ve never made my own. I hadn’t quite realised the extent to which it is simply breakfast in another form – toast, butter, eggs, milk – with a few sultanas scattered over the top. As classic puddings go, it’s refreshingly foolproof – just layer everything into a deep dish, like a lasagne, and bake until set. My family ate this without complaint and, although I’ve always found it disconcerting that actual slices of bread are left sticking up out of it – like the sardine heads poking out of a stargazy pie – I would hate to see it become extinct for that reason.

Taste: 3; ease: 3

Queen of puddings

To be on the safe side, I chose a recipe by the queen of puddings herself, Delia Smith. This is another old bread dessert, requiring fresh (ie stale) white breadcrumbs soaked in hot milk, combined with sugar, egg yolks, butter and lemon zest. The result is baked in an ovenproof dish until it takes on a weird rubbery texture. Then you spread melted jam over the top, layer stiff egg whites on top of the jam, and bake for another 10 to 15 minutes until the meringue peaks are nicely singed.

This was a wholly surprising success – elegant and even a little decadent, although I only had a taste before my wife took the whole thing to a dinner party I wasn’t invited to, and came back with an empty dish. In the circumstances, full marks.

Taste: 5; ease: 4

Treacle sponge pudding

I’m relieved to discover that this contains neither suet or old bread. According to Delia, it’s a sponge batter with a bit of black treacle in the mix, poured into a pudding basin that already has a generous puddle of golden syrup in the bottom, and steamed for two hours. When it’s turned out, the syrup should run down through it in the time-honoured fashion.

My first ever attempt was a little shabby in appearance – some of the sponge clung to the bowl, and I missed the middle of the plate when turning it out – but it was absolutely delicious when accompanied by custard, double cream, clotted cream or, in my case, an unholy combination of the three.

Taste: 5; ease: 4

Flummery

An ancient, jelly-like dessert, flummery is traditionally thickened with the starch that comes from oatmeal soaked in water. This presents two problems from the modern cook’s perspective: first, a full 48 hours of soaking is required before the oatmeal is discarded and the starchy water preserved; and second, even that will not be enough.

“So the flummery refuses to thicken,” is a phrase that could easily come from a 17th-century book of aphorisms. But that’s what happened to me. I stirred the mixture of cloudy oat water, orange juice and sugar for nearly half an hour, and still it doth refuse.

The recipe I consulted says that if your flummery is reluctant to thicken you can add a bit of cornflour, which is another way of saying “warning: this recipe may not work”. A bit of cornflour, I decided, equates to about half a teaspoon. When that achieved nothing, I added another half teaspoon, and another, and another. By that point I was thinking: even if this works, it’s no longer a true flummery.

Suddenly, almost an hour after I started stirring, the mixture turned to glue. I beat in some cream and put it in the fridge, as instructed, to set even further. The recipe is meant to yield six dessert glasses of flummery. My version stretched to exactly one.

However, once I’d added a thin layer of honey mixed with whisky, and a thick layer of piped whipped cream dusted with orange zest, the dessert started looking the part. It even tasted good, although of the three layers, the bottom one – the flummery itself – was my least favourite.

Taste: 3; ease: 1

Spotted dick

This is the last of the suet puddings on the list, and ideally the last one I will ever make. I am getting very good at trussing up puddings for steaming, but progressively less good at eating them – I’m beginning to lose heart.

This is essentially the same old basic suet dough, this time studded with currants, a sort of miser’s raisin. Curiously, James Martin’s recipe leaves out the protective foil layer for steaming – he uses greaseproof paper with a tea towel over the top instead. It sounds risky, but I follow his instructions because I’m not in a position to know if it makes a difference.

The result, however, looks perfect, and tastes exactly as I guessed it would: dry and dull. It’s much better with custard, but not as good as custard on its own.

Taste: 2; ease: 4

Malvern pudding

This one is simple – apples in custard, with a demerara sugar and cinnamon crust on top, like a Worcestershire creme brulee. The Hairy Bikers’ recipe relies on what is essentially a creme patissiere; but if you can nail that part the rest is easy, as well as tasty. It’s also the only one of the 10 puddings here that you could conceivably produce on a whim. Malvern pudding came eighth in a list of the 10 most threatened British puddings back in 2006 (calf’s foot jelly came top), but on this showing it deserves reassessment.

Taste: 5; ease: 4

Cabinet pudding

The historical version of cabinet pudding – or chancellor’s pudding – seems to be another old bread recipe, but the version I made is a fairly ordinary kind of sponge. The gimmicks are the mixed peel added to the dough and the halved glace cherries decorating the sides. You must add the dough a bit at a time, to support each fresh row of cherries along the wall of the basin, otherwise they’ll slip off. It needs to steam for an hour and a half, which in the world of traditional British puddings is a blink of an eye.

I like this one – it looks very impressive, for comparatively little effort, and, like almost all these puddings, it begs to be drowned in custard or cream or both. If you were the chancellor you may feel you deserved more, but I was happy enough.

Taste: 3; ease: 4

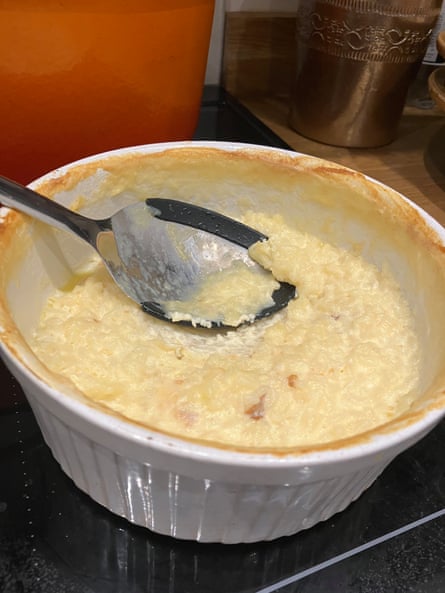

Rice pudding

A confession: I have a longstanding aversion to rice pudding. I can’t call it dislike, because I’ve never actually let any pass my lips. But it doesn’t rise to the level of a phobia either; just a lifetime of saying, “None for me, thanks.”

I trust the food writer Simon Hopkinson in all things, but I’m taking his word for it in this case, since I don’t know what rice pudding is supposed to taste like. He starts his rice pudding on the hob: melting butter, coating the pudding rice (not that easy to come by, but it’s basically paella rice), and stirring in sugar until the rice is swollen and sticky. Add milk – a whole litre – some cream, vanilla and a grating of nutmeg over the top. Bake for between an hour and 90 minutes, depending.

I’m assured by my wife, who likes rice pudding, that this is a very good version. Having tried it for the first time, I can return to my aversion with confidence. At this point, I quite fancy a Calippo.

Taste: 3.5; ease: 5

Of all the puddings tested, I would say that Malvern pudding is most worthy of rehabilitation, and simultaneously the most in need of it. And while I would shed no tears if either spotted dick or Sussex pond pudding became extinct tomorrow, jam roly-poly is one pudding I’d be happy to terminate with extreme prejudice.

3 months ago

130

3 months ago

130