In the weak winter sunshine forensic investigators in white suits cast long shadows as they stepped between gravestones at Playa Ancha cemetery in the Chilean coastal city of Valparaíso.

But as the rhythmic click of spades and the throb of an excavator faded, a third search for the remains of Michael Woodward reached a frustrating conclusion.

No trace has ever been found of Woodward, an Anglo-Chilean priest who is thought to have been murdered on the Esmeralda, a Chilean navy corvette which Gen Augusto Pinochet’s bloody regime used as a floating torture centre after its coup d’état on 11 September 1973.

But almost two years since the Chilean state assumed responsibility for finding the missing victims of Pinochet’s regime for the first time, cautious, methodical progress is being made.

“The fact that they managed to carve out a space for a permanent, ongoing public policy commitment is no mean feat,” said Dr Cath Collins, director of the transitional justice observatory at Diego Portales University in Santiago.

In August 2023, the National Search Plan for Truth and Justice became an official state policy, with the aiming of centralizing information, finding the remains – or trace the final movements – of 1,469 disappeared people, and seeking reparations for their families.

In the harrowing, uncertain days after Pinochet’s coup, Miguel Woodward, as the tall, cheerful priest was known to his Chilean friends, laid low in the valleys around the city.

Born to an English father and Chilean mother in Valparaíso and educated in the UK, he had returned to Chile to become a priest, joining a leftist political movement under the banner of socialist president Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular coalition.

Early on 22 September 1973, Woodward was kidnapped from his home by a navy patrol and taken to the Universidad Santa María, which had become a makeshift detention centre.

He was beaten and submerged in the campus swimming pool, before being transferred to a naval academy and then on to the Esmeralda, where he is thought to have died of the injuries sustained under torture.

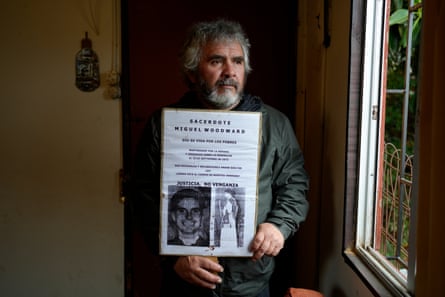

“That’s when our search began,” said Javier Rodríguez, 58, an affable, wild-haired construction worker with an unbreakable will to find the priest he remembers vividly as a family friend.

Rodríguez founded the Friends of Miguel Woodward organisation, and has set up a cultural centre in Woodward’s name, a narrow room a few doors down from where the priest was abducted, where a faded poster promoting the National Search Plan is stuck in the window.

“If Miguel were alive now, he would be marching for Palestine, for the Mapuche [Indigenous people], for all injustices,” he said. “They murdered him because they were afraid of him.”

Since democracy returned to Chile in 1990, human rights cases have made halting progress through the Chilean courts.

Woodward’s sister, Patricia, was able to file a case in 2002, but it was soon closed for lack of evidence. Eventually, when it was reopened on appeal, 10 low-ranking officers were implicated in his torture. Two were convicted, but neither ever served jail time.

Michael Woodward’s final moments have been pieced together from eyewitness accounts and testimonies, but those of many others have not – and activists fear that time is running out.

“The easy cases are all done,” said Dr Collins, “Some of the people who might have been going to talk have died.”

In Chile, the armed forces have long tried to obstruct progress, either by remaining silent or handing over partial or misleading information.

Progress has been achingly slow.

“The state never did enough to find any of the disappeared, but now the resources are there,” said Rodríguez.

“Maybe the [search] plan came late, but it represents the state coming to settle its debts.”

Searches are being carried out at 20 sites up and down the country, but as yet, no finds have been made – and some fear that progress could soon be checked.

“Of course there is going to be disappointment that there haven’t been any big discoveries yet, but if the plan survives the next administration, that’s almost an achievement in itself,” said Dr Collins.

In November , Chileans will vote in a presidential election in which three of the four current leading candidates offer rightwing agendas to replace leftist president Gabriel Boric, who ratified the national search plan.

Woodward’s last home, painted bright blue, still stands on a Valparaíso street corner; neighbours still use “Miguel’s house” as a reference when giving directions.

And despite its dark history, the Esmeralda is still in service in the Chilean navy. It is frequently picketed by protestors at ports around the world, returning periodically to haunt its victims from Valparaíso’s wide bay.

Chile’s forensic medical service says that further searches for Woodward’s body will be carried out in the cemetery in Playa Ancha imminently.

“If we find Miguel, the fight doesn’t end there,” said Rodríguez. “He lived with us and we have a history with him, but he’s just one of those we are missing – there will still be hundreds more to find.”

“We’ll keep fighting until we have justice, whatever that may look like.”

2 months ago

29

2 months ago

29