Studies on gaming’s effect on the brain usually focus on aggression or the cognitive benefits of playing games. The former topic has fallen out of fashion now, after more than a decade’s worth of scientific research failed to prove any causative link between video games and real-world violence. But studies on the positive effects of games have shown that performing complex tasks with your brain and hands is actually quite good for you, and that games can be beneficial for your emotional wellbeing and stress management.

That’s all well and good, but I’m obsessed with the concept of “gamer brain” – that part of us that is drawn to objectively pointless achievements. Mastering a game or finishing a story are normal sources of motivation, but gamer brain is inexplicable. When you retry the same pointless mini-game over and over because you want to get a better high score? When you walk around the invisible boundaries of a level, clicking the mouse just in case something happens? When you stay with a game longer than you should because you feel compelled to unlock that trophy or achievement? When you refuse to knock the difficulty down a level on a particularly evil boss, because that would be letting the game win? That’s gamer brain.

I am not sure whether games cause this very particular flavour of obstinacy, or whether people with obstinate tendencies are drawn to video games. But almost everyone I know who plays a lot of video games is susceptible to it. It’s the part of you that simply will not give in, the part of you that’s determined to bend a game’s rules to your will. The extreme version of it is learning to play impossible DragonForce songs from Guitar Hero at 2X speed, just because you can. Or everything that happens at Awesome Games Done Quick (AGDQ), marathons of joyful gaming pointlessness in which people take on increasingly esoteric challenges, such as playing The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask blindfolded, or speeding through a cursed, modded version of Halo that’s full of random items from other games.

It was this year’s AGDQ, in fact, that got me thinking again about gamer brain, and why we love this stuff. But I also thought about it a lot while playing Baby Steps last year. It’s a game that embraces yet gently mocks the concept of gamer brain – not least through its main character, the useless Nate, who embodies a bunch of stereotypical gamer characteristics, including being totally unwilling to ask for help.

Two of its creators, Gabe Cuzillo and Bennett Foddy, told me a lot about this when we spoke in November. Baby Steps is full of moments that tease you, the player, into attempting ridiculous feats. At several points you’ll find big holes in the ground that you can purposefully fall into, just to see what happens (spoiler: nothing is ever down there). One character warns you away from a tower, telling you there’s no reason to climb it because there’s nothing at the top; of course, I immediately tried to climb the tower. Once, I spent 10 minutes inching my way up a river to a waterfall to see what was behind it; on the rocks behind the water was nothing but a crudely drawn penis.

“There is a normal dirt path by a cliff that you can walk up perfectly safely, and then along the cliff is a series of wooden pegs that you could walk up instead, if you wanted to risk losing 20 minutes of progress,” says Foddy. “That’s a joke that you’re making with the player, because for them to find that funny, they have to know that they’re tempted to walk on the pegs. If the player didn’t feel anything about that other than, ‘Oh, that’s not the correct way to go, I won’t walk on those pegs’, then there’s no joke. But the player gets it because they do want to do the difficult thing.”

The most exquisite joke in all of Baby Steps, for me, comes when you find a pair of glasses that make invisible steps visible. If you decide to try to walk all the way across a bunch of rocky pillars to find these glasses, risking a fall at any moment that would waste perhaps an hour of your time, you will see a path of invisible steps that eventually lead to an invisible trophy. Nate will practically weep with joy in front of this trophy that nobody else can see, calling over a fellow hiker to admire it, who of course can only see Nate dancing around triumphantly in front of absolutely nothing.

“The joke that we keep coming back to is when the player puts themselves in a particular psychological or emotional state and then Nate gets to reflect that in some way,” Foddy says. “You’re seeing yourself reflected in this loser. That’s the deep joke: this guy, this couch potato, he’s actually you in this moment.”

Cuzillo, who also voices Nate, has a chronic case of gamer brain. “Over time, we came around to this idea that a lot of the level design is an opportunity for introspection about why you’re playing the game at all, what kinds of rewards you’re attuned to and why you play games in general,” he says. “You’re asked as a player: What do you care about? Who are you as a person? If you don’t jump into the hole, you’re [left] wondering for the rest of the game about whether you should have jumped in the hole.”

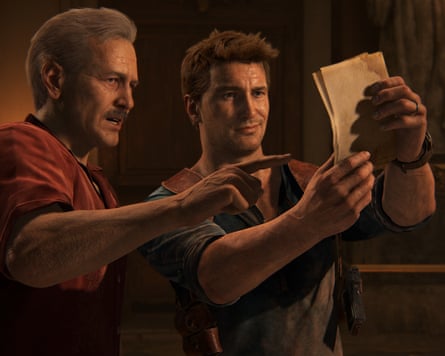

Gamer brain is thought of as a masculine concept, though I can attest that you don’t have to be a man to suffer from it. “I think this is a gendered type of play, toxic masculine play, or at least it’s constructed as such,” Foddy says. “That stuff is riddled through gaming culture. It’s riddled through the kinds of characters that players are asked to embody. Nathan Drake in Uncharted is determined and full of grit, but is that the same thing as being obstinate and dogged and pursuing something stupid?”

Baby Steps is one of those games that you can only truly appreciate if you have a bit of gamer brain in you. Trying to explain why it’s funny is close to impossible – you have to have some understanding of the compulsion and strange transcendence of pursuing pointless objectives. But here’s the key thing about gamer brain, and perhaps about games in general: these things aren’t pointless if they actually mean something to you.

What to play

When I started Sword of the Sea last night and found myself surfing over dunes of tastefully rendered animated sand, I immediately thought of Journey. A lot of this game brings Journey to mind, from the art style and animation to the minimal demands that it makes of you as a player. But you know what? It’s been almost 15 years since that landmark PlayStation 3 game, and it’s been lovely to play something that channels its best moments. You swoosh around the desert, occasionally jumping, occasionally pressing square to make something happen, finding places where your magical sword can bring water back to your arid surroundings. After you’ve flooded the former desert, you surf around on the water instead, ocean creatures flitting around you. It is beautiful, mindful and soothing, if admittedly a little insubstantial; I have found it a comforting, achievable January play.

Available on: PS5, PC

Estimated playtime: 2-3 hours

What to read

-

This week I wrote about playing Hollow Knight: Silksong while living with a chronic pain condition; this beautiful, punishing game has become emblematic of a time when I was thinking a lot about the nature of suffering.

-

Lego’s take on Pokémon has finally been revealed, featuring a £579.99 Kanto evolutions set and a rather unfortunate-looking Pikachu. The Venusaur, Charizard and Blastoise set does look extremely cool, but I do wonder who has the money for incredibly expensive nerd nostalgia toys in this economy.

-

Rockstar Games employees who were dismissed last year in an alleged act of union busting have been fighting the company in court, supported by the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain. After a preliminary hearing in Glasgow last week, a judge has denied the workers’ request for interim relief, meaning that they will not be paid while the legal case is ongoing.

What to click

Question Block

Games correspondent Keith Stuart answers this question, which came in from reader David on email:

My new year resolution is to cut down on Baldur’s Gate 3 and Battlefield and play a few more experimental indie games. But what’s the best way to find them?

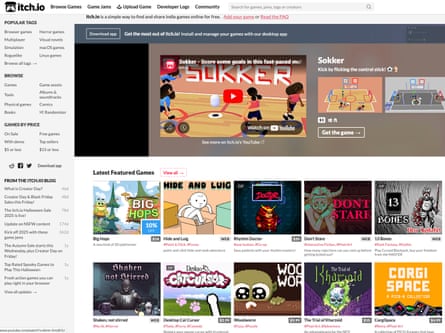

First of all, congratulations on deciding to expand your gaming intake. There’s nothing wrong with blockbuster games, but it’s really lovely to discover brand new – and sometimes incredibly weird – experiences. Aside from the Guardian’s regular indie recs, of course, the front page of digital video game store Itch.io is a good starting point – a lot of smaller developers put their new projects on there and it’s quite well curated. Steam also runs regular indie promotions, including an annual indie festival, and it’s worth watching the annual Indie Game awards, IndieCade and Games for Change for interesting titles. There are lots of review sites specialising in indie titles, too – for example, Indie Game Reviewer and John Walker’s Buried Treasure. Elsewhere, Bluesky is great for following indie developers – there are lots of lists and starter packs to join, which will give you instant access to indie communities. You can search Bluesky’s directory for suggestions. The good thing is, the more indie games you play, the more you get to know the developers and community, and the more new ones you discover.

If you’ve got a question for Question Block – or anything else to say about the newsletter – hit reply or email us on [email protected].

4 hours ago

4

4 hours ago

4