On 6 June, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) conducted aggressive raids in Los Angeles, sweeping up gainfully employed workers with no criminal record. This led to demonstrations outside the Los Angeles federal building. During these protests, David Huerta, president of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) of California, was arrested alongside more than 100 others – leading to even larger demonstrations the next day.

Donald Trump responded on 7 June by sending federal troops to Los Angeles to quell the protests without consulting Governor Gavin Newsom and, in fact, in defiance of Newsom’s wishes. This dramatic federal response, paired with increasingly aggressive tactics by local police, led to the protests growing larger and escalating in their intensity. They’ve begun spreading to other major cities, too.

Cue the culture war.

On the right, the response was predictable: the federal clampdown was largely praised. Hyperbolic narratives about the protests and the protesters were uncritically amplified and affirmed. On the left, the response was no less predictable. There is a constellation of academic and media personalities who breathlessly root for all protests to escalate into violent revolution while another faction claims to support all the causes in principle but somehow never encounters an actual protest movement that they outright support.

For my part, as I watched Waymo cars burning as Mexican flags fluttered behind them, I couldn’t help but be reminded of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In the documentary Sociology Is a Martial Art, he emphasized: “I don’t think it’s a problem that young people are burning cars. I want them to be able to burn cars for a purpose.”

It is, indeed, possible for burning cars to serve a purpose. However, it matters immensely who is perceived to have lit the fuse.

It’s uncomfortable to talk about, but all major successful social movements realized their goals with and through direct conflict. There’s never been a case where people just held hands and sang Kumbaya, provoking those in power to nod and declare, “I never thought of it that way,” and then voluntarily make difficult concessions without any threats or coercion needed. Attempts at persuasion are typically necessary for a movement’s success, but they’re rarely sufficient. Actual or anticipated violence, destruction and chaos also have their role to play.

Civil rights leaders in the 1950s, for instance, went out of their way to provoke high-profile, violent and disproportionate responses from those who supported segregation. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr had an intuitive understanding of what empirical social science now affirms: what matters isn’t the presence or absence of violence but, rather, who gets blamed for any escalations that occur.

The current anti-Ice protests have included clashes with police and occasional property damage. Melees, looting and destruction are perennially unpopular. Then again, so were civil rights-era bus boycotts, diner sit-ins and marches. In truth, the public rarely supports any form of social protest.

Something similar holds for elite opinion-makers. In the civil rights era, as now, many who claimed to support social justice causes also described virtually any disruptive action taken in the service of those causes as counterproductive, whether it was violent or not. As I describe in my book, civil rights leaders across the board described these “supporters” as the primary stumbling block for achieving equality.

The simple truth is that most stakeholders in society – elites and normies alike, and across ideological lines – would prefer to stick with a suboptimal status quo than to embrace disruption in the service of an uncertain future state. Due to this widespread impulse, most successful social movements are deeply unpopular until after their victory is apparent. Insofar as they notch successes, it is often in defiance of public opinion.

For instance, protests on US campuses against Israel’s campaign of destruction in Gaza were deeply unpopular. However, for all their flaws and limitations, the demonstrations, and the broader cultural discussion around the protests, did get more people paying attention to what was happening in the Middle East. And as more people looked into Israel’s disastrous campaign in Gaza, American support plummeted. Among Democrats, independents and Republicans alike, sympathy for Israelis over Palestinians is significantly lower today than before 7 October 2023. These patterns are not just evident in the US but also across western Europe and beyond.

The Palestinian author Omar el-Akkad notes that when atrocities become widely recognized, everyone belatedly claims to have always been against them – even if they actively facilitated or denied the crimes while they were being carried out. Successful social movements function the opposite way: once they succeed, everyone paints themselves as having always been for them, even if the movements in question were deeply unpopular at the time.

Martin Luther King Jr, for instance, was widely vilified towards the end of his life. Today, he has a federal holiday named after him. The lesson? Contemporaneous public polls about demonstrations tell us very little about the impact they’ll ultimately have.

So, how can we predict the likely impact of social movements?

The best picture we have from empirical social science research is that conflict can help shift public opinion in favor of political causes, but it can also lead to blowback against those causes. The rule seems to be that whoever is perceived to have initiated violence loses: if the protesters are seen as sparking violence, citizens sour on the cause and support state crackdowns. If the government is seen as having provoked chaos through inept or overly aggressive action, the public grows more sympathetic to the protesters’ cause (even if they continue to hold negative opinions about the protesters and the protests themselves).

The 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles are an instructive example. They arose after King was unjustly beaten by law enforcement and the state failed to hold the perpetrators to account. In public opinion, the government was held liable for these legitimate grievances and outrage. As a result, the subsequent unrest seemed to generate further sympathy for police reform (even though most Americans frowned on the unrest itself).

Stonewall was a literal riot. However, it was also widely understood that the conflict was, itself, a response to law enforcement raids on gay bars. Gay and trans people were being aggressively surveilled and harassed by the state, and began pushing back more forcefully for respect, privacy and autonomy. The government was the perceived aggressor, and this worked to the benefit of the cause. Hence, today, the Stonewall uprising is celebrated as a pivotal moment in civil rights history despite being characterized in a uniformly negative fashion at the time.

This is not the way social movements always play out. If the protests come to be seen as being motivated primarily by animus, resentment or revenge (rather than positive or noble ideals), the public tends to grow more supportive of a crackdown against the movement. Likewise, if demonstrators seem pre-committed to violence, destruction and chaos, people who might otherwise be sympathetic to the cause tend to rapidly disassociate with the protesters and their stated objectives.

The 6 January 2021 raid on the Capitol building, for instance, led to lower levels of affiliation with the GOP. Politicians who subsequently justified the insurrection performed especially poorly in the 2022 midterms (with negative spillover effects to Republican peers).

The protests that followed George Floyd’s murder were a mixed bag: in areas where demonstrations did not spiral into chaos or violence, the protests increased support for many police reforms and, incidentally, the Democratic party. In contexts where violence, looting, crime increases and extremist claims were more prevalent – where protesters seemed more focused on condemning, punishing or razing society rather than fixing it – trends moved in the opposite direction.

Yet, although the Floyd-era protests themselves had an ambivalent effect on public support for criminal justice reform, the outcome of Trump’s clampdown on the demonstrations was unambiguous: it led to a rapid erosion in GOP support among white Americans – likely costing Trump the 2020 election. Why? Because the president came off as an aggressor.

Trump did not push for a crackdown reluctantly, after all other options were exhausted. He appeared to be hungry for conflict and eager to see the situation escalate. He seemed to relish norm violations and inflicting harm on his opponents. These perceptions were politically disastrous for him in 2020. They appear to be just as disastrous today.

Right now, the public is split on whether the ongoing demonstrations in support of immigrants’ rights are peaceful. Yet, broadly, Americans disapprove of these protests, just as they disapprove of most others. Critically, however, most also disapprove of Trump’s decisions to deploy the national guard and the marines to Los Angeles. The federal agency at the heart of these protests, Ice, is not popular either. Americans broadly reject the agency’s tactics of conducting arrests in plain clothes, stuffing people in unmarked vehicles, and wearing masks to shield their identities. The public also disagrees with deporting undocumented immigrants who were brought over as children, alongside policies that separate families, or actions that deny due process.

Employers, meanwhile, have lobbied the White House to revise its policies, which seem to primarily target longstanding and gainfully employed workers rather than criminals or people free-riding on government benefits – to the detriment of core US industries.

Even before the protests began, there were signs that Americans were souring on Trump’s draconian approach to immigration, and public support has declined rapidly since the protests began on 6 June.

Whether the demonstrations ultimately lead to still more erosion of public support for Trump or continued declines in public support for immigration will likely depend less on whether the demonstrations continue to escalate than on whom the public ultimately blames for any escalation that occurs.

At present, it’s not looking good for the White House.

-

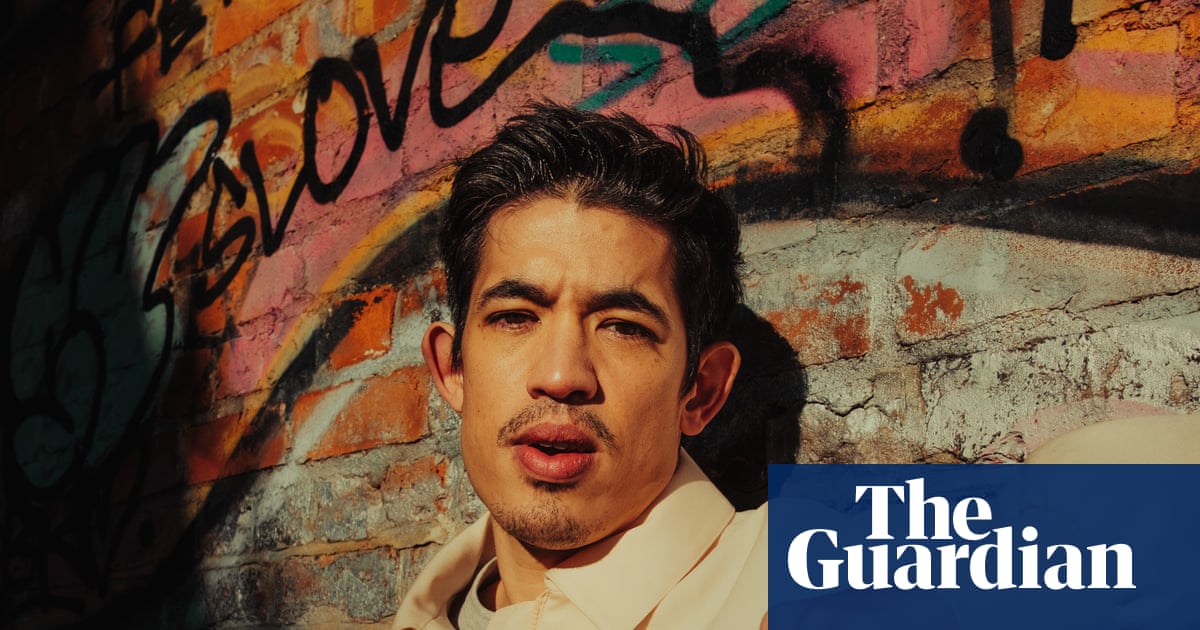

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist in the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University. His book, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, is out now with Princeton University Press. He is a Guardian US columnist

3 months ago

85

3 months ago

85