It’s the eyes that stay with you – piercing black discs that seem to vibrate against the intense orange of a goddess’s skin. The rest is a blur of silver, yellow and saffron as temple attendants encourage you to move, clockwise, around the murti, or sacred statue. For a moment it’s as if this shrine is the one fixed point in the whole city.

The goddess in question is Mumba, the patron of Mumbai, her temple at the beating heart of one of the most densely populated areas on Earth. A few streets to the east is the green and white splendour of Minara mosque. To the north is the intricately carved Jain temple of Parshwanath. All around is the noise and commerce of a place that Indians regard as their version of New York and LA combined – “the city of dreams”. Yet, far from being a godless metropolis, this is a place where religion is very much a going concern.

And, as Sushma Jansari, curator of south Asia at the British Museum in London, explains, it’s not surprising that the eyes have it. Making direct eye contact, getting a glimpse (or darshan) of the divine, is the whole point. For devotees, staring down a god isn’t sacrilegious, but a source of comfort and connection, and a way to ask for help.

Back at the British Museum, Jansari has devised Ancient India: Living Traditions, a mesmerising exhibition that explores the roots of the country’s major homegrown religions – Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. In it, the carvings and statues are all arranged at a height that allows you to meet them face to face: “You actually look them in the eye.” The power of these encounters can transcend religious boundaries. “Whatever your faith,” she says, “when you see a devotional object, it can really affect you.”

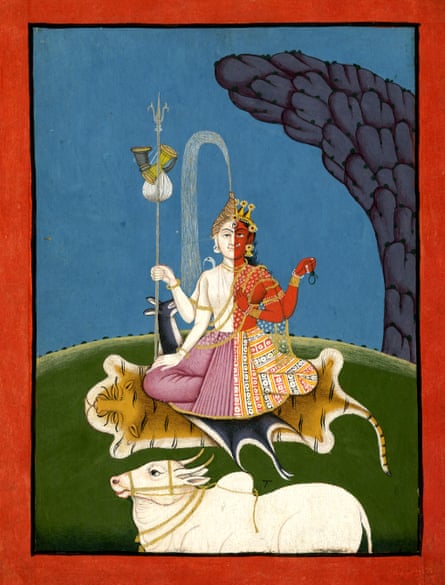

We emerge from the shrine in Mumbai into a covered courtyard that contains, among the stalls selling vestments and offerings, a giant conch shell on a pedestal, its base spattered with vermilion pigment. This represents Vishnu, says Jansari, one of Hinduism’s three principal deities. But, like so many symbols in India, it’s a shared one. In Buddhism, the conch stands for the spread of the Buddha’s teachings; in Jainism it’s the emblem of one of the revered Tirthankaras or teachers. Once you start to notice these common pieces of iconography, which include the lotus, the snake and the lion, you begin to see them everywhere.

That is certainly the case at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, or CSMVS, known until 1998 as the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India. It’s an ebullient Edwardian pile in Mumbai’s Fort neighbourhood, one of a suite of magnificent buildings that form part of the city’s world heritage site. Notable for its Indo-Saracenic style – think the Taj Mahal crossed with London’s St Pancras station – it contains hundreds of objects from the dawn of India’s early religious history. Two of these are being flown over for the British Museum show, where they will form part of a complex story of influence and assimilation.

One reason for the huge overlap between traditions is the environment in which they emerged; the creators of these objects lived incredibly close to nature. In fact, Jansari says, the natural world “plays the underpinning role. If you think about when [the pieces] were made – from the second and third centuries BCE onwards – the subcontinent is very much an agrarian society. There are some people living in cities, but most people live in the countryside, getting their food and resources from forests and land. For them, nature plays such an outsized role in their everyday lives: if the monsoon rains come, then hooray, they can actually eat. If the rains are too strong and wash away all the crops, they may well starve.”

That awesome power is embodied by the figure of the snake, which comes up again and again, representing both the life-giving and destructive aspects of water (they tend to come out when it’s wet), and of course, mortal danger. In many of the sculptures they appear as protectors, the same crown of cobras rearing up behind images of the Buddha or Vishnu. And then there are the nature spirits or Yakshas (male) and Yakshis (female). These figures predate the major religions, but “once you’ve got those native spirits personified, the artists use that imagery to shape the Jain and Buddhist enlightened teachers and the Hindu gods,” says Jansari.

Often tied to trees, some of the earliest Yakshas were more than three metres high. And because they represent capricious nature, “they’re not all lovely, happy, smiling, beatific figures. When you see them, they’re kind of grimacing. They’re very stern. Imagine walking through the forest and coming across one of these three-metre high figures”. No kidding: at CSMVS the awesome Dvarapala Yaksha guarded one of the Buddhist caves at Pitalkhora. He’s a mere 1.6 metres, magnificent in black basalt, his eyes huge, his expression hard to read, but perhaps not entirely benign.

Jansari has used the rich British Museum collection, as well as loans from Mumbai, Delhi and elsewhere, to conjure something of this otherworldly atmosphere in London. But when she was first asked by colleagues to put on a show about India, she wasn’t sure about the idea. “As somebody from the south Asian diaspora, I know the normal thing is to do a devotional art exhibition looking at either Jainism or Buddhist art or Hindu art. And I’m not interested in doing something in that very traditional format.”

Instead, she was determined “that these be represented as living traditions”, with – and this was crucial – total transparency as to how the objects got there. “The collecting history strand absolutely had to be not just an add-on, but an integral part of the show.” Why was that so important? “Nowadays we all want to know how these objects came to be at this museum. Generally speaking, it’s presented in quite a binary way: it’s either good or it’s bad. Whereas actually there is so much more nuance in these stories.”

There are carvings from the Buddhist stupa (a dome-shaped shrine) at Amaravati, for example, including an incredible double-sided relief depicting the monument itself. Most of the archaeological material there was destroyed by local workmen in the 18th century, who ground down the limestone to make mortar. East India Company officials then descended, salvaging some material, yes, but also wrecking it further in the process. The pieces they gathered were sent to the company’s London HQ, and eventually transferred to Bloomsbury where the British Museum is located. In other words: “It’s complicated.” Jansari also mentions a yaksha donated by a collector who was born in what is now Bangladesh. “So he had a lot more agency. It’s not necessarily this kind of colonial story.”

The other thing she insisted on was genuine community involvement. That meant recruiting people from each of the different faiths to discuss those complex collecting histories, and how to treat sacred objects appropriately. As a result of these conversations, the exhibition has avoided any animal products – silk drapes were ditched, and vegan paint used – in accordance with the principle of ahimsa, or non-violence towards all living beings. They also talked about how to respectfully dispose of offerings that devotees might make in the gallery space. “I don’t think it’s weird to look on a devotional object that was created for the purpose of veneration, and [see] people having that experience [in the museum].”

For Arshna Sanghrajka, a pharmacist and practising Jain from London, being invited to take part was particularly meaningful. “I was really excited because museums tend to be very arty-farty. You look at things from the past and you admire their splendour and their beauty. And this was quite different, because while, yes, they wanted to do that, they also wanted a connection with the present.”

That included recognising that these objects are holy to at least some of the people viewing them. “Even the way things were being placed, so, for example, not placing an image of a Tirthankara directly on to a plinth. It should be on a slightly raised platform, which is how it would be worshipped in the home or in a temple – even if that block is just one centimetre thick.”

What emerged was a model for how the legal owners of objects such as these – the museum’s trustees – can effectively widen the definition of whom they belong to. “The way in which museums are engaging with the public is changing,” says Sanghrajka. “For an institution which has so much colonial baggage, it’s really refreshing to see that they are trying to bring the community back into a sense of moral ownership: like, actually these objects are from your faith, from your community, from your geographical areas. They belong to you just as much as they belong to us. I think that’s really special, and I hope that it’s not just limited to this exhibition.”

Bloomsbury is a long way from Mumbai, but Jansari hopes the bright colours (she is particularly thrilled by the “hot pink” of the Hindu section), scent of sandalwood and videos made by community members will give a sense of how ancient traditions remain a vivid part of the present, not just in India, but in Britain too.

“A really important thing for me,” she says, “was to show that this is not all ‘foreign stuff’ – this is now part of our shared cultural heritage. Here in the UK, we have people from all over the world who practise these faiths, we have these stunning, traditionally built temples and religious buildings. And it’s the same with these sacred, devotional images. They’ve been taken around the world for millennia, and now they’ve arrived here.” She pauses. “This idea of moving around, being influenced and influencing others in turn, it’s not a weird, modern concept. We’ve always been doing this. That’s what I want people to take away.”

10 hours ago

8

10 hours ago

8