Four decades ago, my parents were Cambodian refugees. As high school students, they were thrown into one of the darkest chapters of humanity’s history, surviving nearly five years in forced labour camps under the Khmer Rouge genocide. An estimated 2.7 million of my kin perished during that time. Fortunately for my family, they were accepted under Australia’s humanitarian program and arrived in Australia on 26 January, a date heavy with complexity for Australian identity, and our refugee story became another layer within it.

Our journey began when my mother discovered she was pregnant. Together with my father, they decided to flee on foot through landmine-ridden jungle toward the Thai-Cambodian border, carrying nothing but their lives and the hope that their unborn child might escape the suffering they had endured.

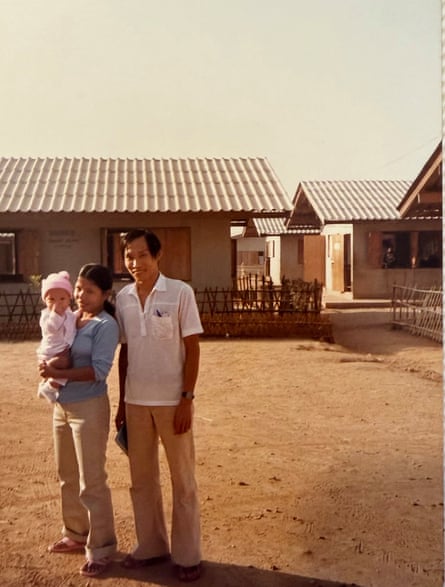

It was there I was born. In a refugee camp shaped by loss, fear and uncertainty.

What met my parents next was not perfected policy or market-based solutions.

It was civil society.

Volunteers from around the world stepped into the chaos where states, borders and institutions had failed. Among them were nurses from the US who gave their time, skill and care in conditions few would willingly choose. One nurse, in particular, took my parents under her wing. She helped them navigate medical checks, paperwork, survival and dignity. She cared for them, and for me, as if we were her own family.

She was from Minneapolis, Minnesota. Four decades later, another Minnesotan nurse would lose his life supporting migrants in distress. Alex Pretti was shot by ICE agents and made the ultimate sacrifice in service to others. His final words were reported to be: “Are you OK?”

I watched this unfold on the news in horror, sitting side by side in front of the television with the nurse who had saved my family’s life. Sandra Evenson, a humble Minnesotan nurse whom I had spent months trying to find nearly a year earlier, was visiting my family in Sydney the week the shooting unfolded. Every morning, she was calling home to check on friends and family and to express how proud she was of the community response.

I was too young to remember her kindness. My life is the evidence of it.

In the chaos of resettlement in Australia four decades earlier, with Sandra’s later relocation to Rwanda, we initially lost contact.

What remained after 40 years of silence were photographs. A small album of black-and-white and grainy colour images, the only record of an era defined by survival against all odds. In many of them, the same woman appeared again and again. My parents would sometimes speak of her: her booming laugh, her relentless optimism, the $50 she pressed into their hands from her own pocket when she learned we had been accepted for resettlement, so they could buy clothes for the journey ahead.

For 40 years, she lived only in my parents’ memory. As they entered their later years, the smiles that once accompanied these photos gave way to long sighs and quiet grief. Like so many nurses, she risked becoming an unsung hero lost to history. I decided this would not be Sandra’s story, and it would not be my parents’ story either. I had to find her.

I searched the internet for Sandra Evenson, which turned out to be an unfortunately common name in the US. I narrowed it down to nurses who had served or studied at one point or another in Minnesota. Of the dozens I called and emailed who fit these criteria, some never replied. Then, one Sunday morning, I opened my inbox to a single-line reply to my long account of our refugee story.

“Yes, this is me. More to come.”

We found each other.

After months of tearful video calls, Sandra decided to make the journey to Australia with her former supervisor from the camp, Patty Seflow. We woke at dawn to greet them after their epic journey from minus-20C Minnesota winter to the heat and humidity of a Sydney summer.

There was no stage and no fanfare. Just a quiet car park at Sydney airport on a bright summer day. A reunion shaped by time, tears and the recognition that some acts of humanity do not expire.

We are living through a time when migrants and refugees are increasingly dehumanised, politicised and reduced to slogans. In the US, aggressive ICE raids, including in Minnesota, have torn families apart in the name of enforcement and spectacle. Fear has become a tool of governance. In Australia, far-right groups are undermining the very fabric of our social and economic success, and one of the cornerstones of our regional security: multiculturalism.

There is a bitter irony here. America’s greatest power was never its military reach or economic dominance. It was its humanitarianism. Its civil society. Its capacity, often paradoxically, to challenge its own excesses through moral courage at the margins. That quiet, decentralised force once stood in tension with America’s impulse to police the world. And that tension mattered. It saved lives.

Today, that legacy is being hollowed out.

In Minnesota, Pretti’s death sits uneasily alongside images of armed raids and terrified families, revealing a painful contradiction.

Nurses are, almost everywhere, the carers of the world in times of crisis. They stitch wounds, hold hands and translate fear into reassurance. They are often invisible. And yet they carry the moral infrastructure of society, and more often than not, our moral compass.

It was nurses who cared for my parents when they were stateless.

It was nurses who cared for me before I had a passport, a nationality or a future anyone could name.

My life exists because someone chose compassion over convenience, service over safety and kindness over borders. Because a nurse from Minnesota followed a moral compass that extended beyond self-interest or nationality.

Pretti’s final question was not political. It was human.

“Are you OK?”

It is a question worth asking ourselves, and our societies, before we decide who belongs, who is protected and who is left to fall. As we watch our American cousins across the Pacific navigate a period of turbulence not seen for generations, it is time to ask it again.

Are you OK?

And, quietly, more urgently: are we?

2 hours ago

6

2 hours ago

6