Daniel Lapin pulls up a video on his phone and, having chatted away for 40 minutes, lets the images do the talking. Or, more accurately, the sounds. It is a scene he captured in the early hours of a Kyiv morning during the spring and what stands out above everything is the awful, incessant, gathering buzz of the Russian-controlled drones that plague Ukraine’s capital almost every night. Sleep is rendered impossible for residents during those attacks, partly due to the sheer noise and in huge degree to the fear that you, or your loved ones, will be struck next. “After a night like that you don’t want to train,” he says. “It can go on five nights in a row. You don’t want anything, you’re just walking around like a zombie.”

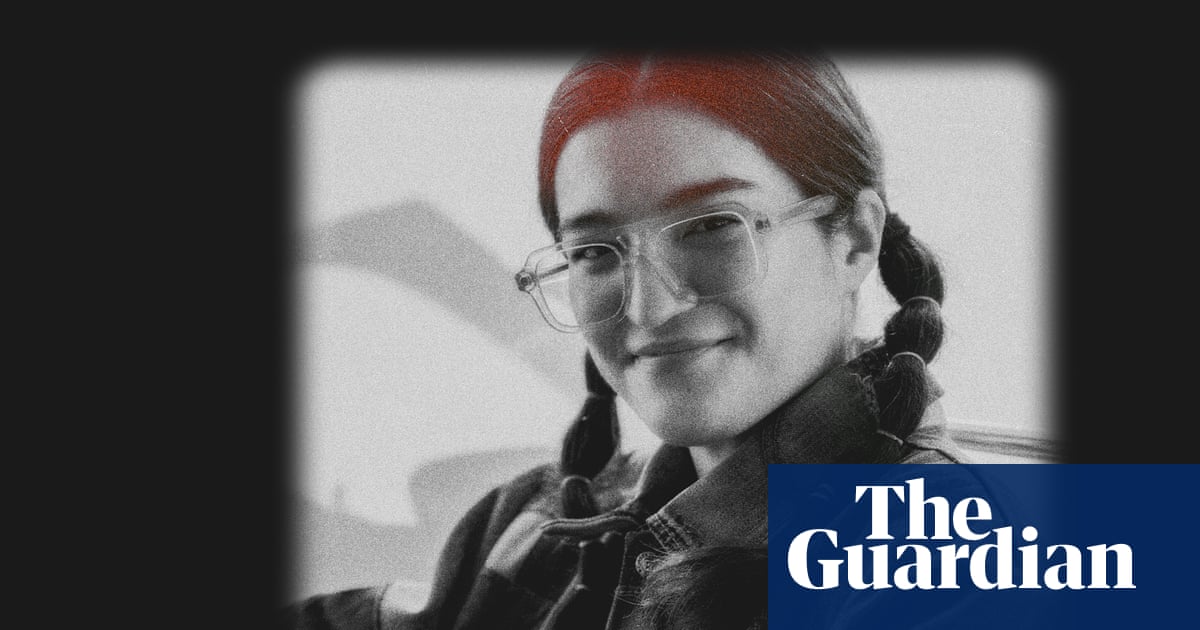

On Saturday, though, Lapin will be fully alert to the task at hand. The light-heavyweight is Ukraine’s next boxing hope, his promise and pedigree immense, and his fight against Lewis Edmondson will be a highlight of the undercard before Oleksandr Usyk and Daniel Dubois contest their undisputed world heavyweight title bout at Wembley. Lapin has seen Russia’s aggression stall his career on two distinct occasions but is closer than ever to carving out a legend of his own.

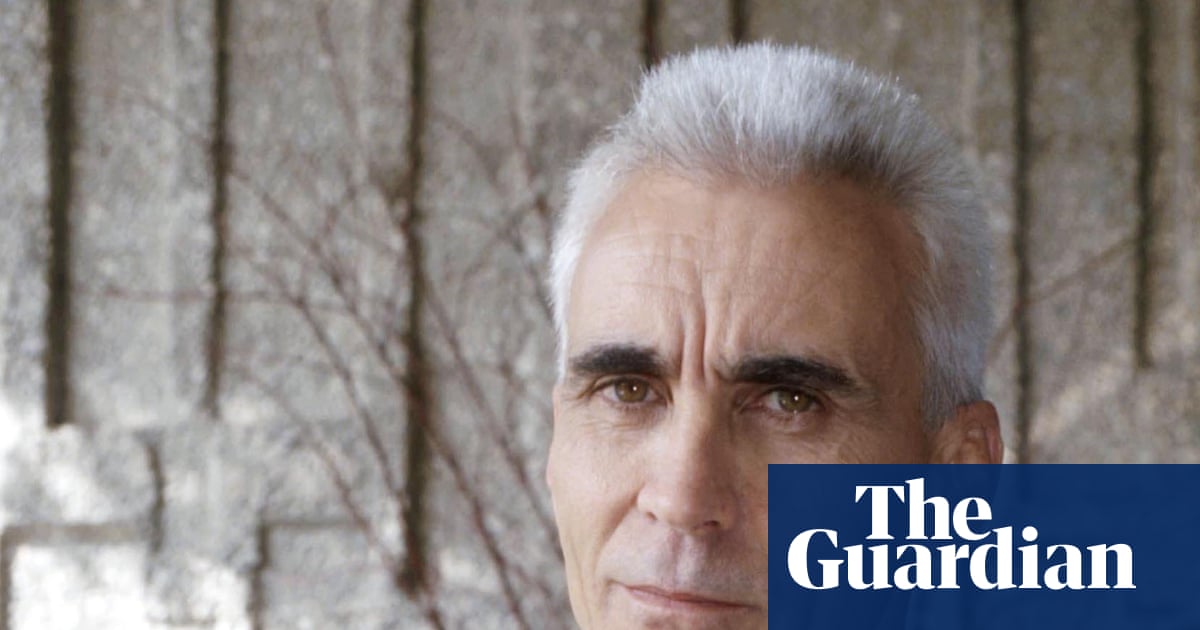

His bond with Usyk is tight. Although born in Poland he grew up in Simferopol, the Crimean city that was also home to Usyk. The superstar has honed a keen appreciation of the younger man’s talent; Lapin is a trusted member of his camp and a regular training partner. “Everything works like a Swiss clock,” Lapin says of the disciplined, intensely motivated regime implemented on the east coast of Spain. No phones are allowed, let alone any social media; news of the horrors that continue to unfold back home barely trickles through until camp members return to the outside world.

It says plenty for Lapin’s mentality that he has progressed this far. In 2014 he was 16 and thriving at amateur level, hoping to compete at the Youth Olympic Games and European Championships, when Russia annexed Crimea and a potentially critical period in his young career was effectively written off. “It had been a very developed boxing scene, hard, a lot of competitors,” he says. “But then Russia destroyed sport in Crimea.

“It became completely cut off from the rest of the world. I was there for three years under occupation and did almost nothing: I only wanted to box for Ukraine. The occupation broke my amateur career. It felt very bad, like a kind of depression.”

Many of his friends became stuck, or went down undesirable routes. Would it not have been easy for Lapin’s life to slide into disrepair, or worse? “I had a dream to become a world champion and I have a mental goal to make it,” he says. “I understood that, if I got into anything else, I wouldn’t be anyone.”

He was eventually able to leave for Kyiv and begin working with Usyk, who his father had previously coached. Lapin’s brother is also Usyk’s team director. The conditions were in place for quick development and, eventually, a winning professional debut in August 2020. He had grown to a towering 6ft 6in, his shape returning after those years out of competition, but the uncertainties of plotting a path to the top remained.

“I lived alone, had very little money, had to organise my own life around training sessions,” he says. “Then when you go to the camp, there’s a strict training regime but you return to your empty flat and have to cook for yourself. You’re looking on YouTube for recipes. I’d cook a huge portion of buckwheat to last a week, but would end up burning it.”

Nonetheless Lapin’s professional life continued to blossom. By the time Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, he had won five of five professional fights, overcoming Poland’s Pawel Martyniuk at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium on the Usyk-Joshua undercard five months previously. The rematch was in his sights when everything became unmoored again.

“I’d just recovered from Covid and was waiting to start shaping up again,” he says. “That morning I got up, there were bangs, the building near us was cracked at the top. In the next four months I lost 11 kilos and it was hard to start training again. Russia disrupted my career twice.”

Once again he bounced back, gathering himself to link up with the camp again and overcome Slovakia’s Josef Jurko in Jeddah that August. Lapin views anticipation, “seeing the punches”, as his biggest strength but plenty of other attributes have amassed since he followed the family example and took up boxing, hesitantly at first, during childhood. He has won all 11 of his professional fights, four by knockout. A world title shot cannot be far off. Usyk is a constant source of encouragement and advice – “He who is afraid dies” is Lapin’s favourite – but he knows that, despite the network around him, the final push comes from within.

“Working with an undisputed world champion doesn’t mean you’ll become one too,” he says. “It doesn’t work that way. In the end it depends only on the fighter himself.”

Lapin’s time has been split between Kyiv, the Usyk camp and London in the buildup to Saturday. On the phone screen he shows more harrowing videos, this time taken by friends in the past week, of drones wailing to a crescendo before exploding close to residential buildings. Wembley will host an occasion that has significance far beyond the sport he loves but he knows at first hand that symbolism will only do a fraction of the job for Ukraine.

“Every activity that highlights Ukraine in the international area is massively important, of course,” he says. “But we are waiting for actions, not only for highlighting.” For Lapin and the rest of the Usyk camp, action is what comes naturally.

3 months ago

72

3 months ago

72