Don’t be deceived by Kate Moss’s Hunter wellies at the entrance. Dirty Looks: Desire and Decay in Fashion showcases clothes that are deliberately distressed and filthy, and will come as a shock to anyone whose idea of a fashion exhibition involves glass vitrines and slick, ambient glamour, or the sort of wildly popular blockbusters put on (and paid for) by brands such as Dior and Chanel.

Perhaps because gloss is regarded as an integral element of luxury fashion, objects such as designer dirty trainers tend to infuriate people. There is only one pair at the Barbican’s first fashion exhibition in almost a decade. But the way Balenciaga’s £1,400 faux-filthy high tops came to be not just widely coveted, but objects that seemed to express the disconnect between high fashion and the real world, is at the heart of this exhibition which presumes that the problem is not fashion rending and besmirching its garments. It’s you for not understanding why that’s exciting.

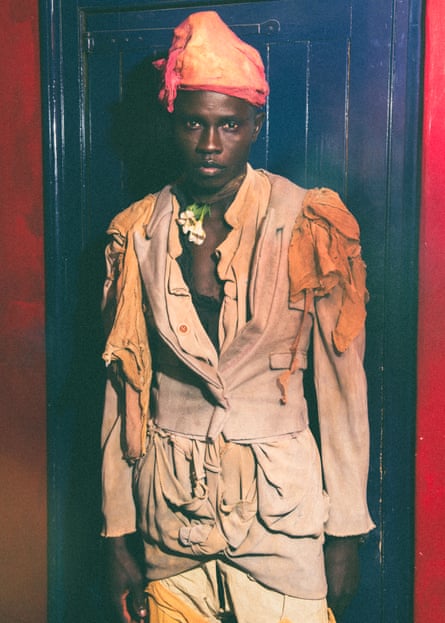

Taking 120 objects – mostly clothes, all filthy – by more than 60 designers both established (the oldest garment is Zandra Rhodes’s safety-pinned wedding dress from 1977) and new (star of London fashion week, Paolo Carzana), the idea is to look beyond simple provocation in order to explore the ways in which contemporary fashion has used dirt, sweat and stains to question western beauty ideals, while exposing the more sanitised side of fashion – mass-produced, internet-sold – as incomparably dirtier by contrast.

Spread out among 12 rooms, each grimier than the last, the dirt in question has three sources: the environment around the clothes, the body within them, and the designers who choose to fake muck rather than waiting for the real stuff to sully their garments. The decay, meanwhile, comes from mice, scissors and time – though there are trompe l’oeil rips too, deliberately placed. Sometimes, in the case of Hussein Chalayan’s folkloric graduate 1993 show The Tangent Flows, the clothes have been subjected to all of the above. The designer buried garments in a friend’s garden then dug them up, a sort of ruin in reverse. The first room is dedicated to seven of his pieces which hang in tatters, too delicate for mannequins. Never intended to be bought or worn, their survival is a stunning retort to our culture of disposable fashion.

The remaining rooms take these two ideas (dirt, decay) and drag them through the mire of punk and grunge to modern fashion. Some items are cringe-inducing – including a dress from John Galliano’s 2000 collection which he said was inspired by the homeless (and which may have inspired the 2001 film, Zoolander). Others, such as Helmut Lang’s 1998 paint-splattered jeans, the Mayflower of distressed denim, seem almost quaint by today’s tattered standards.

Assistant curator Jon Astbury says that he was particularly interested in the “meticulous process of fakery” that goes into fashion. Because there is dirt and designer dirt. Spanish designer Miguel Adrover’s gown was hand-painted with birds and then caked in Nile mud. The besmirching techniques vary between designers, along with what the grime means – Vivienne Westwood’s mud is a trangression of bourgeois sensibilities, while Rei Kawakubo’s is more connected to the natural world and dyeing techniques. Each, however, seems to say something about the way we wear clothes today, and what they mean to us over time.

Among the standout pieces are a Vin + Omi dress made from King Charles’s horse’s hair – he is named as a collaborator – and a Commes des Garçons blackened bridal gown which is preserved, Miss Havisham-like, in a glass box. In a grossout section on bodily fluids, JordanLuca’s urine-stained jeans are worth close examination, perhaps with a clothes peg to hand, while JW Anderson’s pigeon clutch – transforming a filthy pest into luxury fashion – is a smart addition to the show. Sometimes, though, the rooms lack context. Andrew Groves’s razorblade dress, which served as a delightfully provocative riposte to Bill Clinton’s criticism of fashion’s glamourising drug in the 90s, feels slightly tangential without the pastiche cocaine-covered catwalk it first appeared on.

The show takes a perverse but infectious joy in the way some ladle on sludge to garments that are already well-used, and the more decomposed an item is, the better. Take an already-dirty Madame Grès couture gown to which artist Alice Potts has added her own sweat. “It’s about embracing the decay that it had suffered just by the nature of how it was kept and then adding this extra layer of artistic dirt”, says Astbury. There are thousands of gowns which are too stained with smoke and wine to show. Here, as alternatives to the sterilisation of modern fashion, is dirt as proof of a life well lived.

3 months ago

88

3 months ago

88