Yushy was on a packed tube on New Year’s Eve when he heard voices yell his name. He recognised their faces from the squat raves he had been photographing. “We’re going to a party right now,” they whispered. “I have my camera,” he said, and followed them. He didn’t know anything else about them. In the squat rave underground, which thrives on anonymity and secret locations, it didn’t matter. “They trusted me with them, and I trusted them to take me to the rave,” he says.

His new book, Section 63: Underground and Unmastered, documents three years in this London scene. Yushy started out as a fresher when he replied to a party promoter looking for a photographer. But he grew bored with the more mainstream events he was photographing, and started asking attendees about underground happenings. “I also asked around in group chats,” he says, “Which I later found out – once I was inside the official rave group chat – were placeholders for people to be approved. Purgatory, essentially!”

-

Passing a cigarette over the decks.

Once accepted into the scene, Yushy realised that amid multiple UK club closures every week, these squat raves were bringing back the rebellious energy of acid house raves, which which were outlawed in the Public Order Act of 1994: the book is named after section 63, which restricted public gatherings around music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”.

“Thirty years later, things are still awful and the cost of living is rising through the roof, leading to clubs closing,” he says, “Fun is being monitored – but the existence of these raves prove there’s ways to not succumb to that.”

-

Smoking at a rave.

It’s an unwritten rule that there’s no social media at these raves. “You have to pay an entry, but you know it’s a space where you can dance and not be bothered,” he said, “You can sit down with your friends and just chill for a few hours or leave and not worry about how you’re exiting the party.” The constant documentation of had-to-be-there moments in the mainstream, he says, makes letting loose “a lot harder as everyone is trying to create this fear of missing out online”. His work intentionally sits outside that. “I hope it is a visual language where people don’t know where or when the photos were taken,” he says. “I’ve had people come to me saying, oh this party was in 1993. I hate to break it to them.”

-

Following the co-ordinates, and the view from a venue.

Community is key to the scene. Promoters send messages with various locations en route to the party; as hopeful revellers find one another, they group together and receive more coordinates. Once they reach a particular spot, promoters may share a phone number with an answering machine that reveals the final party location. “You may not speak to each other again until the next party, but you listened and trusted each other,” says Yushy.

He feels similar when a party offers drug testing – especially since party drugs became more extreme post-pandemic. “They make people more aware about what they consume,” he says. “Approaching a medical professional, if they wanted [advice on how] to do [drugs] safely, could get them in trouble.” But at one of these raves, he says, “if someone isn’t feeling well, people would offer water, some paracetamol and see if you need help to get home. This level of kindness to your fellow raver isn’t there in the mainstream.”

-

The chillout zone under a bridge.

The risk of police turning up and unceremoniously pulling the plug also means scene members have to keep their wits about them. Once, when some ravers didn’t recognise Yushy and objected to him taking photos, they pulled a knife – then he showed them his Instagram account and they realised they had mutual friends. And when police entered a party one night, he could easily have shown his press card and got away. But if he did that, he says, “all my credibility is lost. We all left together, and I fell into a deep puddle while running away. I got rid of the card that day.”

-

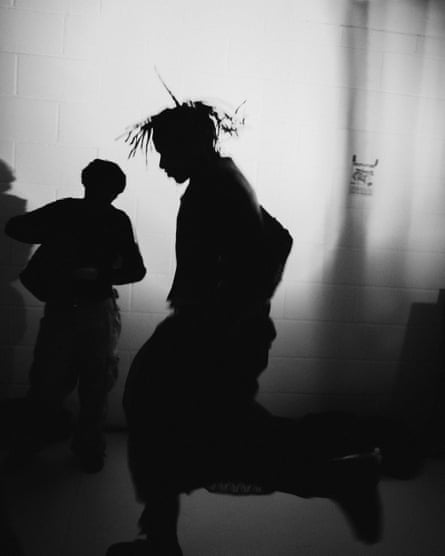

A dancer in silhouette.

Of course, shady promoters exist, sometimes dashing out the back of a building with a box full of cash from the entry fees. “You suddenly find yourself in an empty warehouse with no music and an empty speaker system that doesn’t work,” says Yushy. “And there’s no chance to know until you’re through the door. But it’s also about being adaptable for me.” In one photograph, a couple kisses on an empty dancefloor. “I took that after the promoters ran out. It’s a uniquely intimate moment that they’re having between them, despite the circumstances. It made it worth what happened.”

Spending time in these empty premises also offers bleak insight into cultural closures and property ownership interests in the capital. Often, says Yushy, you arrive at a party location and realise you’ve been there before, in the space’s former life. One rave was in a former cinema. “It became apparent it had closed a few months prior because of bankruptcy. It felt strange and familiar.”

-

Dancers in front of speakers.

Or, he says, parties take place in London buildings in hip parts of town that have been lying empty for two decades. “Which is crazy,” he says. “It could be turned into flats, but the landlord refuses. Sometimes promoters would enter a commercial building and have people who are homeless around the area keep the building occupied until a party, after which they leave the building as they found it. They’re doing more than any landlord or business-owner will for any community around them.”

3 months ago

86

3 months ago

86