Shakespeare’s drama about the double standards of despots who are drunk on their own power was of course going to resonate with our times. Director Emily Burns puts these strongmen in slick modern-day suits to hammer it home and the parallel becomes all the clearer in Frankie Bradshaw’s set which resembles a political battlefield of glass, chrome and parliamentary green. But the production also lays bare how puritanical morality and religion are weaponised by politicians in ways that seems utterly applicable to the machinations of the right wing today.

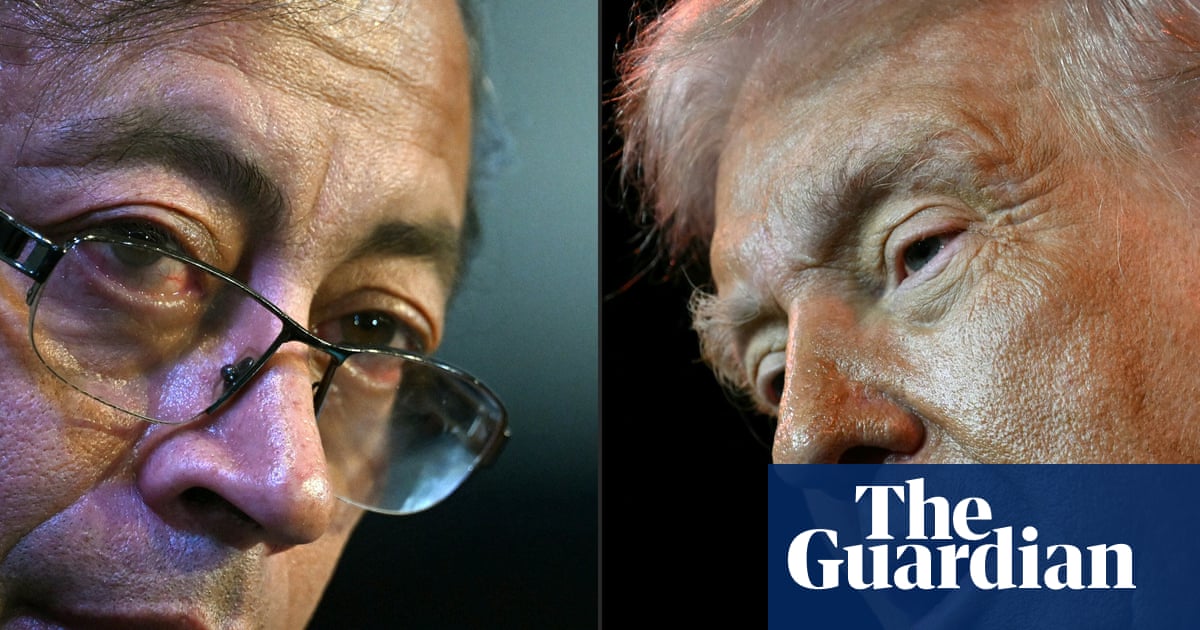

An opening screen montage designed by Zakk Hein includes leaders whose reigns have been rocked by sex scandals (such as Bill Clinton and Donald Trump) as well as images of Jeffrey Epstein and Prince Andrew. What is ingenious, and counterintuitive, is that the villainous Angelo (Tom Mothersdale) is still made human. Outwardly he has an accountant’s dead-eyed way, following his morality laws to the letter by sentencing Claudio (Oli Higginson) on a technicality: he is waiting for dowry matters to be resolved when he is caught in flagrante with his wife-to-be, Juliet (Miya James). But when Angelo proposes to Claudio’s sister, Isabella (Isis Hainsworth), that he spare her brother’s life in exchange for her virginity – effectively blackmailing her for sex – he is shown to be tormented by his desire. You are repelled by his bald hypocrisy but understand it arises from weakness.

What also seems so modern in the production is the doubt cast on women’s testimonies. “Who will believe thee?” Angelo says, when she threatens him with exposure, knowing the world will take his word over hers. Recent plays such as Red Like Fruit and Prima Facie illustrate this fact, and it is truly horrifying that Angelo’s words ring so true today.

This razor-sharp production has crisp, clear direction. A major high-wire edit is made by Burns who cuts the entire subplot involving Elbow, Mistress Overdone and co. It becomes a solemn play, with no distraction or light relief from the central storyline, but that works in its favour, with tension and dread turned up and up. Single notes of music (composed by Asaf Zohar) recur and spotlights heighten them further (lighting design by Joshua Pharo), along with unexpected use of Elvis Presley’s Can’t Help Falling in Love to accompany the vital bedroom swap between Isabella and Mariana (Emily Benjamin). The sex is made explicit and surprising in its power games.

Even in spite of the excision of the more comic scenes, the production manages to wring out humour from certain lines spoken by these men, for their hypocrisies: Angelo’s shame at the end is both terrible and ridiculous as he tries to hide himself under his jacket like a naughty schoolboy, while Lucio (Douggie McMeekin)’s attention-seeking interruptions – and lies – during Duke Vincentio’s returning speech are laughable.

Each performer brings fullness to their part, with crystalline verse delivery. Every inflection of Adam James’s Duke resembles that of a power-playing politician. Hainsworth, as Isabella, begins as the wide-eyed novice nun – a kind of Christian Dorothy of Oz with her gingham dress and scrubbed-face sense of right and wrong – but reveals steel and anger to become a mighty force. Benjamin’s hard-faced Mariana is another highlight but it is Mothersdale who soars the highest in making Angelo both appalling and human.

The women’s testimonies do triumph over Angelo’s in the end albeit with the vital help of the Duke. This production navigates his queasy marriage proposal to Isabella, which usually carries the sense of yet more sexual coercion, with an open-endedness that is more satisfactory for our times – and possibility brings Isabella her much-earned liberation.

3 months ago

74

3 months ago

74