In the polarised climate of British politics, irritation with Liberal Democrats is one of the few things that Labour and Tory MPs have in common. Parliament’s two biggest parties see each other as arch enemies – status that affords some mutual respect. The Lib Dems are treated more like pests, ideological shapeshifters, wheedling their way into voters’ affections, burrowing into local politics. If allowed to nest in a constituency, they are notoriously hard to shift.

Kemi Badenoch has a severe infestation in her back yard. Of the 72 seats currently held by Ed Davey’s party, 60 were taken from Conservatives. The former seats of three Tory prime ministers – David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson – are now represented by Lib Dem MPs. That pattern was repeated in this year’s local elections, when the Lib Dems gained 163 seats almost entirely at the Tories’ expense.

Badenoch shows no inclination to fight back, nor any comprehension of why her party surrendered its heartland. Earlier this year she dismissed Davey’s troops as people who “don’t have much of an ideology other than being nice”; the sort of busybodies “who are good at fixing their church roof”.

Such disdain for undogmatic civic engagement explains why the Conservatives, who once defined themselves as little platoons fired by that spirit, are slumped in irrelevant torpor. It gives Davey hope of advancing further into areas with a critical mass of voters who were amenable to the Conservatism of Cameron or May, receptive at first to Johnson’s bonhomie, latterly disgusted by his mendacity and appalled by the chaotic aftermath. Dismay turns to alarm at the sight of Tories shrivelling and hardening in cowardly imitation of Reform UK.

Davey’s keynote speech at this week’s Lib Dem conference in Bournemouth led with an invitation to make common cause with “millions of one-nation Conservatives who reject the divisive politics of Badenoch and Farage”.

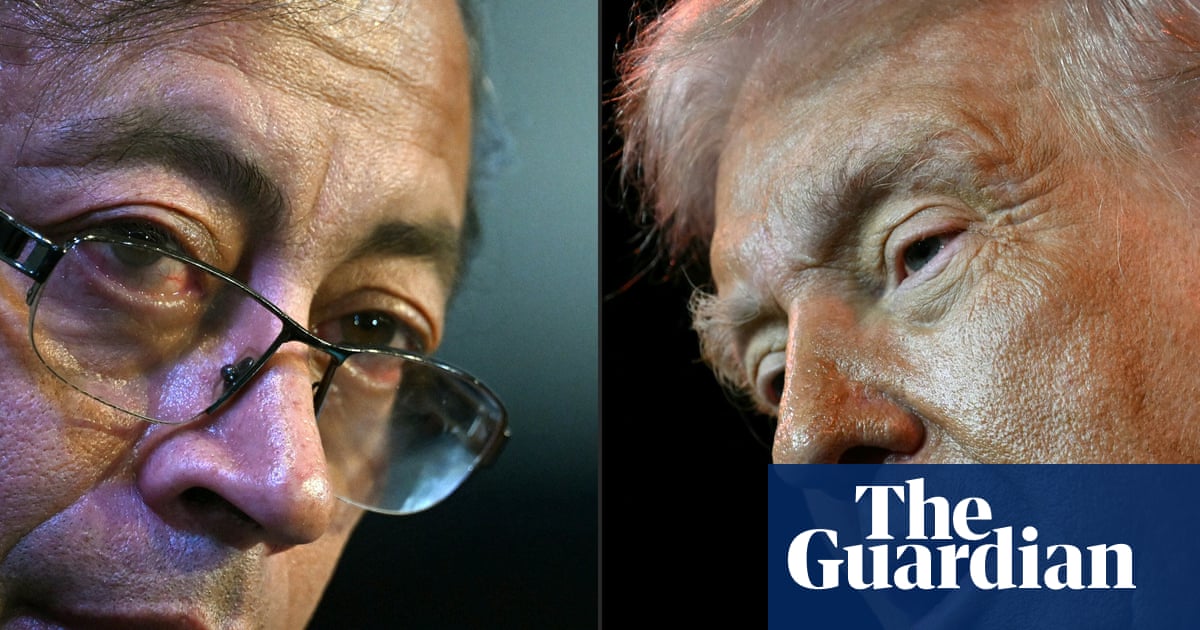

The Reform UK leader is central to the pitch because he embodies a style of politics that horrifies Davey’s target audience, galvanising an electoral coalition that would otherwise lack coherence.

Alongside queasy centre-right ex-Conservatives, the Lib Dems need to recruit more left-leaning voters who might support them out of tactical necessity, or who backed Keir Starmer in 2024, hoping for muscular social democracy, and feel demoralised by his compromises in office.

It is a familiar conundrum for a party with a history of poaching seats by tacking alternately left and right in opposition to whatever the incumbent government happened to be doing. Davey knows the dangers of weather-vane opportunism. He was one of 49 Lib Dem MPs blown out of the Commons in 2015 by the typhoon of voter scorn for a party that had swapped pious leftish opposition under Labour for cosy cabinet jobs under a Tory prime minister five years earlier.

Last year’s success at borrowing millions of votes from Labour supporters to turf out Tories suggests the sin of coalition has been expiated. The passage of time helps. A bigger factor is the seismic disruption of Brexit, scrambling allegiances and burying grudges.

For many remain voters, pre-referendum politics now appears in rosy retrospect as a time of general moderation and rationality.

Liberal democracy, broadly defined as support for institutions and cultural norms that uphold individual freedom, representative government and the rule of law, was the undisputed mainstream consensus. There were plenty of liberals on Labour and Conservative benches. The party that wears the doctrine in its name seemed sometimes otiose.

Brexit changed that. It was a nationalist programme. The pseudo-liberal free-trading school of Euroscepticism soon revealed itself to be nothing more than a lobby for subordination to America-first protectionism. The cause of liberal democracy started to look imperilled in Britain, as it has across Europe and the US.

The Lib Dems briefly looked like the nation’s primary electoral vehicle for expressing alarm at that trend and grief at separation from the EU. They came second to Farage’s Brexit party in the 2019 European parliament elections.

Then they wildly over-reached with a pledge to revoke the commitment to leave, dispensing even with the courtesy of a second referendum – an affront to democracy that made even passionate remainers flinch. The subsequent general election was settled by Johnson’s double appeal as purveyor of a quick fix to get Brexit done and the man who would stop Jeremy Corbyn entering Downing Street. It was another near-extinction event for the Lib Dems.

after newsletter promotion

Since his voter base is stacked with ex-Conservatives, Davey can’t risk evangelical Europhilia, but he leans further into the economic case for re-integration than Starmer. His conference speech restated the policy of a customs union to put Britain “on a path to the single market”.

More significant was the Lib Dem leader’s readiness to cite Brexit as evidence of Farage’s general unfitness for office. He was, as Davey said, “champion” for the cause. That ought to be an electoral liability when a majority of British people now judge it on a scale from disappointment to calamity.

An even clearer majority dislike Donald Trump. Farage’s enthusiasm for the US president – on a personal level and as a model for aggressive xenophobic policy – is a clear vulnerability for Reform UK; an open goal.

But Starmer dribbles delicately around the box for fear of causing offence in the White House. Badenoch is stuck at the back of the stands, chanting for a more cerebral, less popular brand of populism. That has left Davey clear to take the shot. His speech outlined the contest between a “silent majority” of moderate, compassionate patriots who actually like their home country, and Faragist fanatics who hate modern Britain and would twist and fold it into Trump’s America.

This argument can be pressed hard without fear of alienating potential supporters. Lib Dem MPs aren’t at risk from direct voter traffic to Reform. There is hardly any overlap between the two parties’ intended audiences and their existing backers barely even consider switching from one to the other. That clarifies Davey’s task as a project to organise the local anti-Farage coalition in target seats. It brings a relatively sharp focus to a party whose identity has often been blurred as a function of showing different faces in different seats, depending on the party of the closest local rival.

The old contradictions aren’t ironed out. Lib Dems participate in the same fiscal fictions as everyone else. They demand costly improvements in public services while complaining about tax rises. They reject any budget measure that grazes the wallets of their affluent suburban and rural voters and spend hypothetical revenue from growth to be generated by unexplained economic alchemy.

But there is no ambiguity on the question of what kind of country Britain wants to be; whether we want to see the finely interwoven sinews of cultural diversity and social tolerance picked apart by sharp-suited thugs and vaporised under flamethrowers of Trumpian demagoguery. In the lost era of liberal democratic consensus, it wasn’t always clear what the point was of a party called the Liberal Democrats. Now they have an urgent cause to align with their name.

-

Rafael Behr is a Guardian columnist

3 months ago

69

3 months ago

69