It’s 11 years since Sarah McLachlan last released an album of original songs. The break had worried her. “What do I have to say at this point in my life?” she says. “I’m a 57-year-old white woman of privilege. Does anybody want to hear from me?”

Looking tanned and relaxed on an early morning video call from Vancouver Island, the Nova Scotia native admits she had “stayed busy”: she released a Christmas album (2016’s Wonderland) and worked as the principal fundraiser and founding board chair for her three namesake music schools, which provide lessons and education to at-risk youth. At the same time, she was a self-proclaimed dance mom raising two daughters; the second recently went off to college. But there was still “trepidation around being out of the game for so long”.

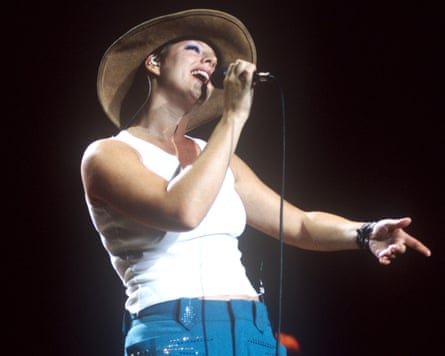

McLachlan, though, has never been one for reticence. In the 1990s, with her otherworldly voice and knack for cathartic lyrics, the three-time Grammy winner was part of a galvanising movement of bold female singer-songwriters, from Alanis Morissette to Fiona Apple and Indigo Girls. Her US breakthrough, 1994’s Fumbling Towards Ecstasy, contained the haunting single Possession, based on obsessive fan letters she received.

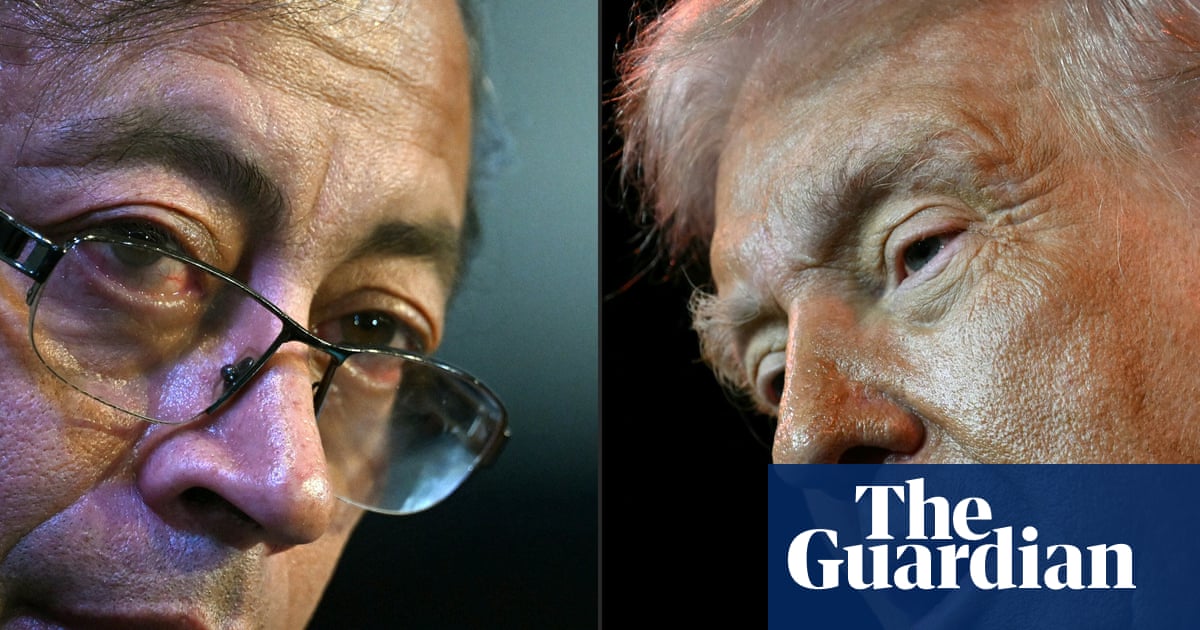

Several years later, she founded Lilith Fair, a revolutionary all-female artists festival that upended the music industry’s gendered power dynamics. At this week’s premiere of a documentary about the festival, Lilith Fair: Building a Mystery, McLachlan castigated the “insidious erosion of women’s rights, of trans and queer rights.” A subsidiary of Disney is distributing the documentary, and Disney’s temporary suspension of Jimmy Kimmel’s talk show over his comments about Charlie Kirk prompted McLachlan to refuse to give a previously announced live performance “in solidarity in support of free speech”. On his return to TV this week (23 September), McLachlan was his musical guest.

McLachlan’s honesty and willingness to subvert the status quo inspire intense devotion. Feist, Allison Russell and Muna’s Katie Gavin (who appears on Better Broken’s Reminds Me) are avowed fans. (You may not be aware of your own devotion: she sang the gutting When She Loved Me from Toy Story 2.) The rapturous response to a recent anniversary tour where she performed Fumbling Towards Ecstasy in full was “overwhelming”, she says. “I had no idea that many people had such an attachment to that record. Everybody I got to talk to about it was like, ‘Oh my God – this record got me through my first year of university.’”

In recent years, McLachlan started trying to work out her next musical steps. She scrapped a bunch of songs, but found her direction with Rise, a song about embracing community when facing political headwinds. She wrote One in a Long Line, a steely response to the erosion of women’s rights and the overturning of Roe v Wade. “That song is about being mad,” she says with a laugh. “And upset, and going, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ I’ve never been overtly political. But I feel like this is a time where I have a platform, and whether I alienate fans or not, I feel like I need to make a stand.”

The song acknowledges the generations of women who “fought so hard to put [things] into place so that we would have agency over our own bodies,” she says. “To see that being taken away – and to see this idea that we should be back to being barefoot in the kitchen serving our men – is terrifying and enraging.” But she wanted to channel anger into action and interrogate the roots of these attitudes – “Is it just fear? Is it control?” – in order to “figure out a way forward” for future generations. To underscore this point, her two daughters add poignant backing vocals. “Because it is more about them than it is about me,” says McLachlan. “It’s about the generations coming forward and what we’re creating for them and what the world’s going to look like.”

Growing up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, McLachlan first took ukulele lessons from a neighbour and later studied classical guitar and piano at a conservatory. “It was never the kind of music that I was that interested in, but it was a means to learn the instruments,” she says. “So I stuck with it.” She preferred listening to her mother’s folk records (Cat Stevens, Joan Baez, Simon and Garfunkel) and soon gravitated toward more progressive music. Genesis’s 1974 LP The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway was “a seminal record” – she gave one of her daughters the middle name Rael, the album’s main character – while Peter Gabriel, Cocteau Twins and Kate Bush became influential touchstones.

At 19, after being spotted fronting her short-lived band the October Game, McLachlan signed with the Canadian indie label Nettwerk Records. They gave her “autonomy” and “full creative control” over her work. “Which is amazing,” she says. “I had no idea how lucky I was.”

These halcyon days were short-lived. When she started promoting her music to radio in the 1990s, stations told McLachlan her single couldn’t be playlisted because another female artist had already been added that week, or that they couldn’t play two women back to back. Naturally, that didn’t apply to male artists. “It just seems so asinine to me,” she says. “As a music fan, I would just listen to music. I wouldn’t even think, ‘Is it a guy or a girl?’”

Determined to prove the narrow-minded gatekeepers wrong, McLachlan booked a handful of all-female concerts in summer 1996. These shows sold out; buoyed by the enthusiasm, she started Lilith Fair the following year. The touring festival featured a rotating multi-stage lineup packed with mainstream and underground artists – the first year included Fiona Apple, Suzanne Vega, Tracy Chapman, Emmylou Harris and Sheryl Crow – and benefited local women’s charities.

Promoters and radio employees were sceptical, she says, telling her: “People won’t come if you put more than two women on stage together.” But the tour became a phenomenon – and fringed with anti-abortion protesters and threats of violence. She held exhausting daily press conferences before each date, fielding questions that forced her to defend the tour’s very existence: “‘Why are you doing this? Why do you hate men?’ And I’m like, ‘What does celebrating women have to do with hating men?’” The constant pushback was “surprising and shocking to me at the beginning”, she says now. “And it wore me down a little bit, because I’m like, ‘You want to rip this thing apart, and you probably haven’t even come to see it.’”

Lilith Fair raised McLachlan’s profile considerably. “I was playing to probably 3,000 people before I did Lilith,” she says. “And all of a sudden I was playing to 15, 18, 20,000. My audience exploded, and all the other [Lilith] artists’ audiences exploded as well.” By the end of the third and final Lilith Fair in 1999, McLachlan was itching to make new music, but found it increasingly difficult to balance overseeing the festival with songwriting. Musical trends had also shifted, with alt-rock earnestness replaced by regressive nu-metal and glossy pop.

She enjoyed a massive UK hit in 2000 with dance remixes of Silence, a collaboration with her then-labelmates, the ambient electronic group Delerium, but over the next decade her commercial fortunes cooled. A 2010 Lilith Fair revival was marred by lacklustre crowds, negative headlines and financial woes.

But today, momentum is on McLachlan’s side. Silence became a perennial summer dance staple. “A friend texted me last night from Burning Man,” she says. “It’s like, ‘Here’s your song with [DJ] John Summit.’ It’s had legs.”

That long-awaited documentary on Lilith Fair also premieres this month. The film deftly illustrates the festival’s radical joy by juxtaposing new commentary from McLachlan and other artists (Jewel, Liz Phair, Indigo Girls, Paula Cole) with archival news, performance and interview clips. The artists come across as principled and full of integrity despite facing frankly horrifying sexism and misogyny; the artistic community that sprang up around Lilith Fair was clearly an oasis from this treatment.

During filming, McLachlan re-read her diaries from this era and was struck by the juxtaposition of creative euphoria and operational stress: “So-and-so is not showing up. We’ve got a bomb threat.” She was gratified that the film itself captures the positivity of the tour. “I really got a sense of the joy, the exhilaration of meeting all these artists, of getting to perform with them, of getting to create bonds and friendships and this community that wasn’t competitive,” she says. “[It was] a safe space for us as artists, a safe space for the audience.”

Many younger artists have called for the return of Lilith Fair, but McLachlan is ambivalent – and content to let those acts evolve her legacy. “It was all-encompassing, overwhelming,” she says. “And we did it – I already did it – so now I don’t want to do it again. Someone else can take the flame.”

3 months ago

76

3 months ago

76