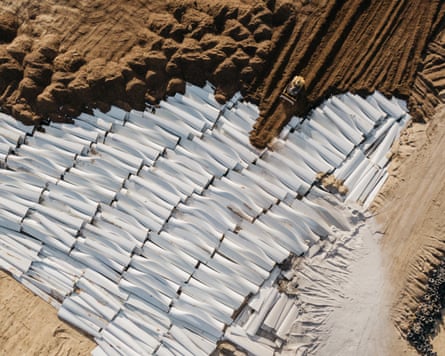

In the Scottish port town of Irvine in Aryshire, almost 80 of Britain’s oldest wind turbine blades lie disused in an old warehouse.

Thirty years ago they towered 55 metres above the South Lanarkshire countryside, powering Scotland’s first commercial windfarm at Hagshaw Hill. Today, they wait for a green energy breakthrough of another kind: blade recycling.

Where they once stood, a clutch of 14 newer turbines have taken their place. They are larger, more powerful, and will generate five times more green electricity than the originals while taking up less space.

Elsewhere in Europe, similar plans to “repower” the continent’s oldest windfarms with more efficient turbines and more powerful blades are under way, increasing clean power generation. However, this green revolution brings a fresh sustainability challenge for the industry as companies consider what to do with the thousands of obsolete older models.

About 85% to 90% of a wind turbine is made from steel and other materials that can be easily recycled. However, the carbon fibre blades, designed to withstand the wear and tear of the elements, are more difficult to break down.

The race to find a way to recycle old turbine blades needs to progress apace. By 2030 Europe is expected to dismantle about 14,000 wind turbines, creating 40,000-60,000 tonnes of blade waste, according to WindEurope. Germany alone will account for approximately 23,300 tonnes, followed by Spain with 16,000 and Italy with 2,300.

The US wind power industry is expected to follow suit. By 2050 the government expects wind turbine blade waste to range from about 200,000 to 370,000 tonnes a year as windfarms approved under the Biden administration reach the end of their lives.

Today, most of the world’s established windfarm developers have vowed to avoid their old blades ending up in the ground. However, the fact that some of the world’s oldest turbines have been dumped in landfill has raised concerns over the industry’s sustainability credentials.

Opponents of wind power have seized on the dilemma of what to do with old turbines. Donald Trump, who has made his loathing for the technology clear, claimed that wind turbines “start to rust and rot in eight years”.

The US president said during his visit to Scotland in July: “You can’t really turn them off, you can’t burn them. They won’t let you bury the propellers, the props, because there’s a certain type of fibre that doesn’t go well with the land.”

Those claims have been dismissed by experts and those working towards new ways to reuse old turbines. Steven Lindsay, a blade recycling entrepreneur in Scotland, told the Guardian “the reality isn’t as President Trump described”.

He said: “Decommissioning old windfarms is about managing an infrastructure transition that transforms yesterday’s clean energy assets into tomorrow’s raw materials.

“We’ve been using circular economy principles to repurpose and recycle the blades into valuable products for years – from using whole blade segments as high-impact public realm infrastructure like shelters, to extracting the fibres for remanufacture into something new.”

The former employee of ScottishPower, which owns the Hagshaw Hill windfarm, struck a deal with the rival developer SSE to use retired blades from its older windfarms as shelters for electric vehicle charging points in Dundee. Bus shelters and bike shelters made from turbine blades are on offer, too.

However, the vast majority of turbines will not have the option of being repurposed. ScottishPower’s parent, the Spanish energy company Iberdrola, believes it may have a solution that could work at scale.

after newsletter promotion

The company said earlier this summer that its new blade recycling facility on the Iberian peninsula would be able to transform up to 10,000 tonnes of blade waste a year, or a sixth of the total waste expected by 2030.

The project aims to recover the glass fibres and resins used to create wind turbine blades and reuse them in sectors such as energy, aerospace, automotive, textiles, chemicals and construction. In this way it could continue contributing to the energy transition and promoting the circular economy in Spain, the company said.

Mario Ruiz-Tagle, the chief executive of Iberdrola Spain, said: “We are inaugurating much more than an industrial plant. We are inaugurating a new stage in the circular economy of renewable energies. This factory, the first on the peninsula dedicated to recycling wind turbine blades, is a concrete response to a challenge that is already here.”

Across the industry, companies including ScottishPower, SSE and Denmark’s Ørsted have promised to work closely with government bodies and industry associations to develop a new generation of wind turbine blade that is easier to recycle and the recycling facilities to get the job done.

An Ørsted spokesperson said: “If it takes longer than anticipated to find recycling solutions that are both environmentally sustainable and commercially viable, we will store any decommissioned blades temporarily to save them from landfill.”

In the meantime, the industry is working with experts to extend the lives of Britain’s existing turbines to delay the need for long-term storage. The Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult, a government-backed innovation body, has started work with the renewables developer RWE to replicate real-world conditions in its testing lab with the aim of figuring out how to extend the life of the UK’s existing blades, and delay the need for recycling.

Lorna Bennet, a senior sustainability engineer at the ORE Catapult, said: “With about 500 offshore wind turbines in UK waters due to reach the end of their original intended lifespan in the next five years there is an urgent obligation to not only think about how to increase the number of installed wind turbines generating clean energy, but to consider how we can extend the lifespan of current turbines and their components.”

The early results of this testing suggests that wind turbine blades could have their lifetimes safely extended by half, in what could prove a step-change for the industry.

This would come too late for the blades from Hagshaw Hill, which are destined to wait in Ayrshire for a recycling solution for Britain’s blade challenge – perhaps providing another milestone for the UK’s green economy.

3 months ago

109

3 months ago

109