Bubble tea and all-day brunch, those reliable cultural signifiers for the social media age, seem as much in evidence in Budapest these days as old-school belle époque coffee houses and tourists queueing for Danube cruises. There’s something else new in the EU’s only one-party state: politics has returned.

For 15 years, Viktor Orbán’s electoral victories have been a foregone conclusion. But a credible political challenger to Orbán has appeared. Péter Magyar is no messiah: in fact, he is a defector from the ruling Fidesz party. But polls show Magyar and his new-ish pro-western Tisza movement are on course to defeat Orbán in April elections.

Such an outcome would not just be a big deal for Hungarians. After years of Orbán’s obstructionism within the EU, its future, and that of European democracy more broadly, is also at stake.

Hungary is what Hungarian political analysts such as Péter Krekó call an “informational” autocracy. This means Orbánism deploys more artful ways to gag critics and maintain its grip than locking people up. Spinning populist narratives to turn public opinion against “liberal elites” is at the heart of how Orbán has maintained far-right populist rule for 15 years – at the expense, many would say, of the rule of law and democracy, even beyond Europe.

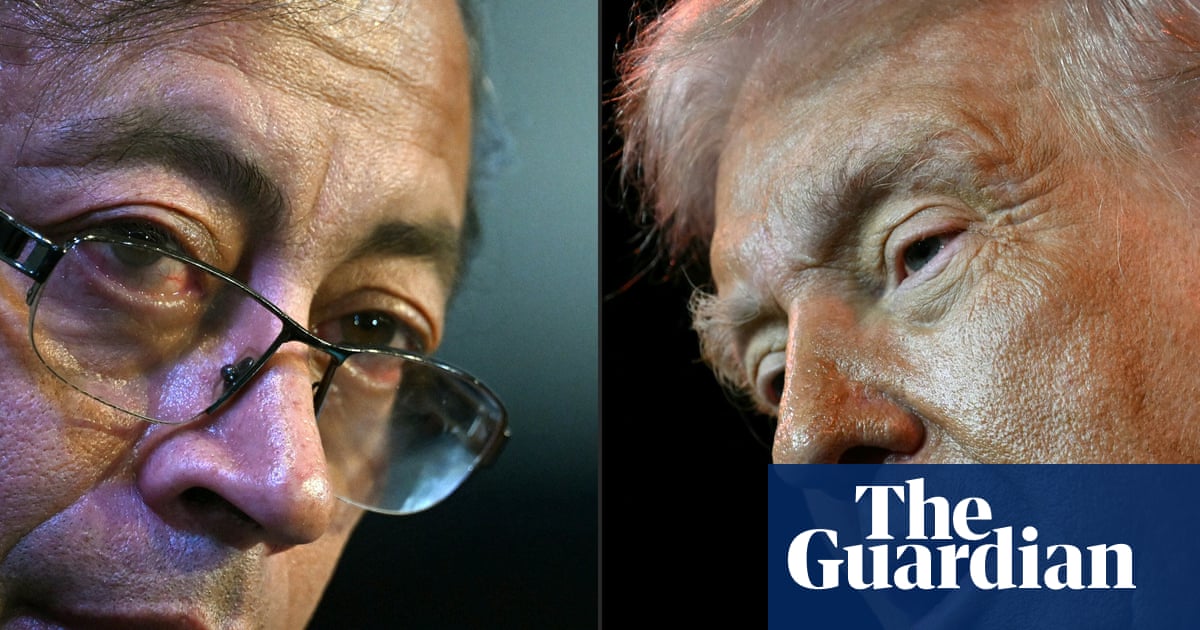

Orbán’s model – curtailing the independent media and fighting culture wars, while slicing away constitutional checks and balances – may have provided Donald Trump with a blueprint for the assault he is accused of launching on the democratic system in the US.

“I watched it happen in Hungary, now it’s happening here,” an ex-US ambassador to Hungary warned in a New York Times column recently. Democracy Noir, a new Connie Field documentary about Orbán, is being talked about as essential viewing for Americans because of the parallels it highlights between the Trump and Orbán methods.

Repackaged Maga ideology is now boosting Europe’s insurgent parties on the populist right, in a remarkable feedback loop. Andrej Babiš, an ally of both Orbán and Marine Le Pen in France, is tipped for a return to power in the Czech Republic next month. Poland recently elected a nationalist president. And in the UK all eyes are on Nigel Farage’s Reform.

Orbánism is seen by many as the connecting thread.

Backlash in Europe’s populism laboratory

The Central European University could stand as a monument to Hungary’s fate as a laboratory for reversing democracy. Once a symbol of academic freedom and liberal thought in post-communist eastern Europe, its Budapest campus has no students. In 2017, Orbán passed a law forcing the George Soros-affiliated institution into exile.

The former lecture halls were busy last week though, as the capital’s progressive mayor Gergely Karácsony – a thorn in Orbán’s side – hosted a “democracy forum” and warned politicians from elsewhere in Europe to start defeating “the narratives that make people support populists”. Whether Hungarians themselves are ready for non-populist answers to their problems remains to be seen.

“Orbán fatigue” is prevalent, according to the academic Zsuzsanna Szelényi, a former politician, even in the PM’s rural voter base. But the urgent issue for most people is the economy. Orbán is increasingly viewed as out of touch, with a growing gap between his conspiratorial, EU-baiting public discourse and people’s day-to-day conversations, which are dominated by high food prices, healthcare and endemic corruption.

While a backlash against the cronyist “Orbán system”, in which oligarchs run much of the economy, is not new, what is new is opposition energy. “We have had a leadership crisis for 15 years and that is over. That is what gives Magyar a chance,” said Szelényi.

Katalin Cseh, an opposition MP, whose own party has decided not to contest the election to maximise chances of Orbán being unseated, agrees that Magyar’s centre-right policies are ill defined. “But we share a strong belief in restoring democracy and ending systemic corruption,” she said.

Weakened … but don’t write him off

Orbán has won four consecutive elections by a landslide. Underestimating him would be foolhardy.

Nevertheless, Krekó, director of the independent Political Capital thinktank, detects a crack in the “total confidence” that has long typified the regime.

Orbán’s attempt to ban Budapest Pride in June backfired. The march was the biggest ever, thanks in part to Karácsony – a massive show of rainbow flags and anti-government defiance.

Krekó also cites a Fidesz wobble over a “chilling, draconian” bill that would have blacklisted organisations with any foreign connections. It has been put on hold, one theory suggests, because of internal Fidesz concerns that it could backfire on them.

“This shows the government is weaker than before; the economic situation is dire; in opinion polls it is lagging behind Tisza; diplomatically within the EU its lack of allies has become quite desperate,” Krekó said.

Yet, Orbán commands a formidable armoury. A suite of generous exchequer-funded enticements, such as top-ups for pensioners and tax cuts for mothers of two children or more, can be expected.

“In 2022, Fidesz spent 6% of Hungary’s GDP in transfers which people received before the elections. A lot of women and nobody under 25 pays income tax any longer. We can expect more of the same this time,” Szelényi said.

after newsletter promotion

Campaigns demonising “enemies of the people” to discredit the opposition are another tried and tested method, Szelényi said. In the 2018 election, fears were whipped up by linking refugees to terrorism. This time, it is Ukrainians; Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s face appearing as an enemy alongside Ursula von der Leyen on posters. Magyar is implausibly portrayed as an agent of Kyiv.

“Orbán’s methodology is all about narratives and storytelling and threats and emotions,” Szelényi said. “Interestingly, migration is no longer discussed. By 2019 it was a non-issue because, of course, in Hungary we need migrants.” State-sponsored agencies have quietly recruited hundreds of thousands of migrants from the Philippines and Vietnam to fill job vacancies.

Game of drones

Orbán’s head-spinning geopolitical contortions – simultaneously friends with Trump, the Kremlin and China – could work against him, or help him remain in power.

Hungary is a Nato member state. Russian military provocations, such as the incursion by Russian fighter jets into Estonia’s airspace, could make Orbán’s proximity to Putin awkward to defend. Even Trump is now saying Nato should shoot down Russian aircraft.

Some Hungarians, including Karácsony, would like an end to Orbán’s ambivalence on Russia. “My great-grandparents were taken away to forced labour camps by Russian soldiers and they never returned alive. There are many such stories engraved in the soul of Hungarians,” he said.

On the other hand, energy deals keep cheap Russian oil and gas flowing – for now – to Hungarian consumers.

Trump may be wary of Hungary’s ties to China. But Orbán’s courting of Beijing guarantees investment, while “China gets a Trojan horse in the European Union” in exchange, Katalin Cseh said.

The fight to shape the narrative

In the claustrophobic basement rooms of Budapest’s Terror House – where visitors get the Fidesz-approved narrative of 20th-century Hungarian history – a video plays on a loop: it is a leaner, younger Orbán, delivering a speech about the evils of foreign invaders, to rapturous applause.

Szelényi knew Orbán well in the 1990s, when they were both in the early Fidesz leadership team and the party was on the liberal-centre. She quit as he radicalised the party, but remembers his reaction to defeat in the 2002 election. “That’s when he became very angry; he thought it was unjust, and the fault of the liberal elites in the media. It became a kind of bug in his head.”

Now that his Christian nationalist ideas have made him the spiritual leader of a global Maga movement, would he accept electoral defeat at home? She has a hard time imagining it. “Orbán does not want defeat. He has completely reorganised the Fidesz campaign and has put himself in the lead.”

New EU rules prohibiting political advertising on social media come into effect next month, but Fidesz is organising its own online army, to spread the Orbán message in so-called digital “fighters clubs”. Szelényi sighs, contemplating the battle for control of the narrative. Whoever can seize it, will win, she said.

“It will be a brutal campaign.”

3 months ago

79

3 months ago

79