From the Thin White Duke to Ziggy Stardust, the Berlin recluse to the late-career elegist, David Bowie’s oeuvre is defined by reinvention. As an artist, he was relentlessly attuned to the conditions that might provoke the next creative rupture. One defining moment, however, has largely slipped from the popular imagination: a day spent inside a psychiatric hospital on the outskirts of Vienna – one that would prove unexpectedly formative.

In September 1994, Bowie and Brian Eno – who had recently reunited to develop new music – accepted an invitation from the Austrian artist André Heller to visit the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic. The site’s Haus der Künstler, established in 1981 as a communal home and studio, is known internationally as a centre for Art Brut – or “Outsider Art” – produced by residents, many living with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders.

The acclaimed Austrian photographer Christine de Grancy documented the visit, capturing Bowie engaging with these so-called “outsider artists” – a term often criticised for framing artists through illness or marginality rather than authorship. For the first time, these intimate portraits will be shown in Australia, when A Day with David opens at Joondalup festival in Western Australia in March, in collaboration with Santa Monica Art Museum.

Through de Grancy’s lens, Bowie’s admiration for the artists is palpable. He crouches, listens, sketches, studies – his attention directed not toward the camera but toward the artists themselves.

“They paint without any feeling of judgment,” Bowie told music journalist Gene Stout in a 1995 interview published in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Whatever they feel is what they paint.”

The visit became a conceptual trigger for 1. Outside, Bowie’s dense, unsettling 1995 album, whose fractured narratives and moral ambiguity were partly shaped by the ideas he encountered there.

Among the artists Bowie met that day, August Walla made a particular impression. Walla’s work – layered with symbols, invented languages and obsessive repetition – extended far beyond paper, covering the walls and facade of the Haus der Künstler. By contrast, Oswald Tschirtner, who lived at Gugging for decades, worked with radical restraint, producing spare pencil drawings in which the human figure was reduced to elongated lines.

“The stunning, rather cold atmosphere of the place is overwhelming,” Bowie told Stout. “You have to drive past the regular asylum before you get to their wing, which is completely covered in paint. They’ve painted every nook and crevice, the walls, all the trees outside. Everything that’s standing and still, they’ve painted.”

When Bowie and Eno returned to the studio to make 1. Outside, they tried to emulate Gugging’s spontaneity and freedom. Bowie later recalled that the first thing they did was “get all the musicians together and make them redecorate the studio,” turning a rehearsal space into something more akin to the painted walls of Gugging. “They got into it so much that it was hard to get them into the music. What it did was give the whole thing a sense of play, which is a part of real freedom of expression.”

Gugging itself carries a darker weight. Founded in the 19th century, the clinic was later absorbed into the Nazi’s Aktion T4 program, which targeted those with mental and physical disabilities, and resulted in the mass murder of an estimated 250,000 people. At Gugging alone, hundreds of patients were murder or sent to extermination facilities.

That history – of institutional violence towards the mentally ill – sits jarringly alongside Gugging’s reinvention as a haven for creativity. Bowie, whose own family life had been marked by mental illness, would have felt that tension acutely. His half-brother Terry Burns, who lived with schizophrenia and died by suicide, haunted much of Bowie’s work.

At Joondalup Contemporary Art Gallery, A Day with David will unfold as more than a conventional photography exhibition. Curated by Lisa Henderson, it will feature 28 framed black-and-white works by Christine de Grancy alongside large-format photographic prints and a video component comprising vintage televisions stacked on internal plinths, playing archival footage as part of the installation. The exhibition also includes a full-scale recreation of August Walla’s painted room, with his iconography covering the walls from floor to ceiling.

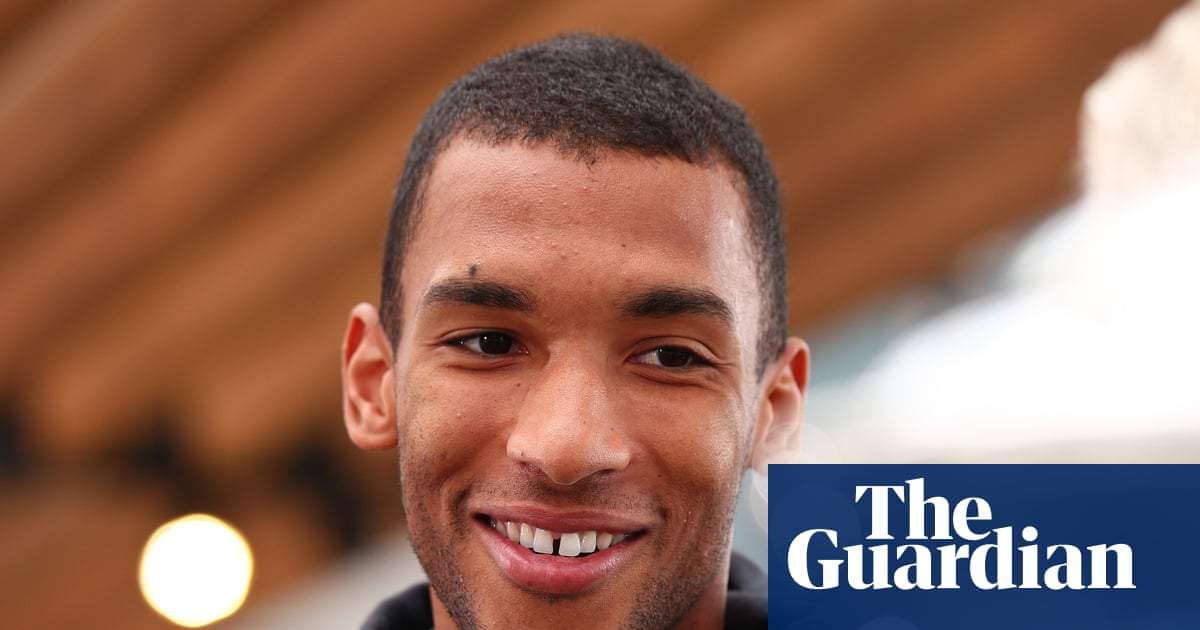

Sadly, Christine de Grancy died on 20 March 2025, just weeks before A Day with David opened at the Santa Monica Art Museum. After sitting in her archive for nearly three decades, the photographs were only brought together as a coherent body of work at the very end of her life. What they offer, the general manager of the Santa Monica Art Museum, Ricardo Puentes says is not celebrity or voyeurism, but proximity. “They feel very candid,” he says. “You don’t feel like you’re looking in. You’re invited into the space.”

Speaking in a video recorded for a 2023 exhibition at Museum Gugging, Christine de Grancy described Bowie as “the star – the world star – who was so completely understated. That kind of presence is not something I associate with stardom at all. He was very withdrawn, extremely observant.”

What the photographs ultimately show, as Puentes puts it, is not a star at all: “It’s really not about him being at the forefront. It’s him being open to other people’s experiences.”

-

A Day with David opens at Joondalup Contemporary Art Gallery on 7 March, as part of Joondalup festival

1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3