A new year is upon us. Traditionally, we use this time to look forward, imagine and plan.

But instead, I have noticed that most of my friends have been struggling to think beyond the next few days or weeks. I, too, have been having difficulty conjuring up visions of a better future – either for myself or in general.

I posted this insight on social media in the final throes of 2025, and received many responses. A lot of respondents agreed – they felt like they were just existing, encased in a bubble of the present tense, the road ahead foggy with uncertainty. But unlike the comforting Buddhist principle of living in the present, the feeling of being trapped in the now was paralyzing us.

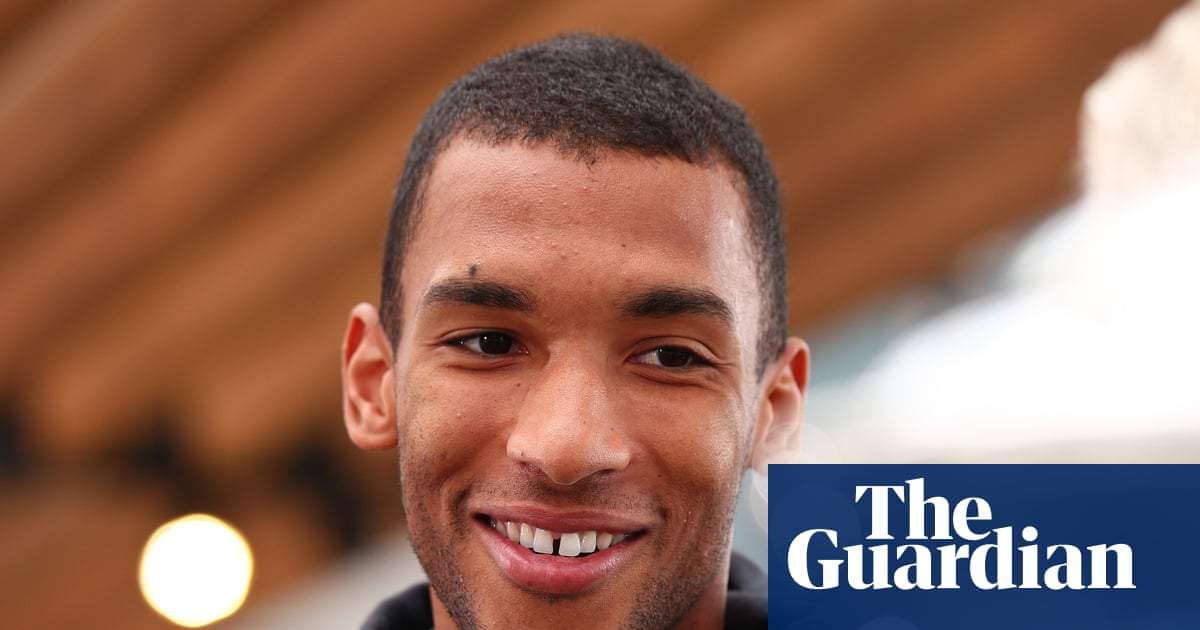

I mentioned this to my therapist, Dr Steve Himmelstein, a clinical psychologist based in New York City who has been practicing for nearly 50 years. He assured me I was not alone. Most of his clients, he said, have “lost the future”.

People are feeling overwhelmed and overstimulated, bombarded with bad news each day – global economic and political instability, the rising cost of living, job insecurity, severe weather events. This not only heightens anxiety but also makes it more difficult to keep going.

I hadn’t fully grasped how much the idea of a better future sustained me – how it made life more livable, hardship more bearable and creativity possible. When I could readily imagine a world that was more just and healthy, it was easier to commit to long-term projects and to invest in the next generation. But in our current political and environmental context, that vision has grown hazier – and I, like many others, have found it much more difficult to be productive and plan for the future.

When I asked Himmelstein if our current inability to think about the future is unique, he said it seems worse now than in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. He spoke to other psychologists in his peer group to gather their impressions.

“Clients are less optimistic now and they don’t talk about the future that much,” Himmelstein reported back. “The consensus is that people don’t seem to feel that good about their lives now. There’s a lot of despair. I have a few clients who don’t really have plans anymore. And when I ask my clients about what they’re looking forward to, most have no answer. They’re not looking forward to things.”

Himmelstein was one of the last students of famed psychologist Viktor Frankl, a concentration camp survivor, professor and author of Man’s Search for Meaning. Himmelstein learned from Frankl that to survive and thrive, we need to believe in a stable, brighter tomorrow. During his darkest days, Frankl was able not only to accept the reality of the suffering around him, but to refocus his attention on the larger meaning of his life. It was this “tragic optimism” that protected him from losing all faith in the future.

When I asked Himmelstein what Frankl might have thought about current events, he paused to reflect. “I think it would scare him,” he said, “like it’s scaring all of us.”

How crisis affects our ideas of the future

Human brains weren’t originally built for thinking about the future – and we’re still bad at it. If clients are struggling with this, Himmelstein asks them to daydream about their lives one or two years out in a more perfect world. “The future is their homework,” he said.

But it’s not easy. Our biology is, in a sense, working against us.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, we are not designed to be thinking about a very distant future,” said Dr Hal Hershfield, a psychologist and professor of marketing and behavioral decision-making at UCLA.

In fact, we don’t really think about our future – we remember it, said Hershfield, who studies how humans think about time and how that influences our emotions and behaviors. When we daydream or envision ourselves at a later point, we essentially create a memory. We then use these memories to construct our ideas about the future. This process is called “episodic future thinking”; it supports our decision-making, emotional regulation and ability to plan.

The type of radical uncertainty generated during times of crisis, where all the factors that might affect future events or outcomes are unknowable in advance, interferes with our ability to recall those futures. That makes it harder to predict what will happen and makes calculating accurate probabilities feel nearly impossible.

Humans have been here before, Hershfield reminded me. For example, people living through the Cuban missile crisis had no clear way of knowing if they – or the world itself – would survive.

“What feels very different in the present moment,” Hershfield said, “is that it feels like it’s coming from multiple fronts. It’s everything from political uncertainty in the US and elsewhere, health insecurity from the very fresh memory of a global pandemic, job insecurity from AI, geopolitical insecurity, to environmental insecurity.”

All these crises are happening contemporaneously, and because they interact with each other, their effects pile up. Social scientists refer to these stacked crises as a polycrisis. During a polycrisis, radical uncertainty becomes rife.

The lack of predictability creates more doubt about the future, which blocks our ability to imagine ourselves in it. In a recent study, participants were asked to write down as many future possible events for themselves as they could. Those who were reminded that the future is uncertain produced 25% fewer possible events than control subjects and took much longer on the task. They also rated their thoughts as less reliable. Just thinking about uncertainty made it more difficult for them to remember all their hopes and plans.

The prefrontal cortex – the part of the brain responsible for thinking about our future selves – is one of humankind’s last evolutionary additions, said Dr Daniel Gilbert, a professor of psychology at Harvard who studies how humans navigate the concept of time. Simply put, our species hasn’t been able to conceptualize the future for all that long.

Gilbert has spent decades studying and writing about how bad we are at predicting the future and how our future selves will react to it.

“One problem is that we don’t imagine events correctly,” Gilbert said. “The larger problem is that we don’t know who we will be when we are experiencing that event.”

We rely on the idea of a stable, continuous future self to help us understand the present and to achieve a sense of greater purpose, making it easier to plan and make decisions, said Hershfield. We lean on the idea that the future will resemble the present, at least to some degree. Then we use our predictions to shape the present – for example, brushing our teeth to avoid cavities, planning dinner while we eat breakfast.

It may be harder to plan when we feel insecure about what’s coming. In a series of recent small studies, when people were reminded that the future is radically uncertain, it lowered their self-certainty as well as their feelings that life itself is meaningful.

How other cultures have dealt with uncertainty amid crisis

Dr Daniel Knight, an anthropologist at the University of St Andrews, has been thinking about how humans understand the future for years. While doing fieldwork in Greece during the 2008-2010 debt crisis, he observed how people coped during an extended polycrisis.

“Greece had a migration crisis, an energy crisis, an economic crisis,” Knight said. “I was working with people born in the 1980s and 1990s, who were born into stories about modernity and progress and a very capitalist idea of accumulation. And almost overnight, all of that was stripped from them.”

Suddenly, the future that Greek citizens had grown up believing was inevitable was no longer possible.

Instead, Greeks looked to history for familiar scenarios and outcomes. “Almost overnight narratives switched from planning weddings and holidays, taking out loans, to talk of returning to times of hardship – particularly the 1941 great famine,” said Knight.

In response to the debt crisis, in 2010 the Greek government passed the first austerity bailout package – focused on drastic spending cuts and increased taxes. In response, people began making comparisons to life during the Axis occupation in te second world war. The comparisons helped people not only see that their current crisis could be overcome, but that a brighter future might emerge from it.

Another coping mechanism involved recentering on much shorter timeframes. “Some of them hunkered down in the now,” Knight said. They refocused on themselves, immediate family and friends, only making short-term plans. Knight noticed that more people turned to their community for help in reimagining their lives, and in the process created what Knight calls micro-utopias. Cycling clubs sprang up everywhere, and people made more effort to spend time together.

I recalled that something similar began to happen in New York City as we emerged from pandemic lockdowns. Friends and colleagues were joining community gardens or running clubs, organizing community programs and meetups, and volunteering.

Knight is working on a book on Europe from 1644 to 1660, a time of great strife: the Great Plague, an economic crisis, the burning of Constantinople and London, fears of a new ice age, and a religious crisis in England. The end result of this turmoil was, as Knight said, “a more democratic form of governance and decentralized power, a spreading out of economic risk, and improved sanitation”.

Importantly, Europeans learned to listen to their experts, and funneled more resources into their new universities to support science and the humanities. In sum, the polycrisis of the 1600s gave birth to the Enlightenment.

It’s another reminder that we’re not so special and the times we’re in are not so unprecedented. “Our problems may be different now,” Knight said, “but there is still hope. We have a chance to choose which future we want. And depending on which version we choose, that transforms our actions today. We can make choices and collectively work towards that future.”

How to get the future back

It may be hard to envision distant, positive outcomes amid a crisis, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. “We’d be foolish to stop planning,” said Hershfield. “We can still think about the values that are important to us and plan around them.” So if you know you want to support your child’s college education, for instance, you can still try to build up to that – as much as is possible during tough economic times.

But it’s also important to be more flexible about those plans and have compassion for ourselves. Copious uncertainty from multiple directions can cause us to regret past choices, cautioned Hershfield. It’s not unusual for people to think about what they should have been doing 10, 20 or even 30 years ago to better prepare for this timeline. “That feeling can be paralyzing,” he said, “and it can make us just bury our heads in the sand.”

When something isn’t working or an unexpected event knocks plans off course, it’s OK to shift gears. And if you’re feeling overwhelmed and anxious about what might happen, Hershfield suggests that it’s better to refocus on events that will most likely happen. This makes it easier to remember the future self we envisioned and plan accordingly.

As a new year begins, it’s good to remember that we are more resilient than we think.

“People are not the fragile flowers that a century of psychologists have made us out to be,” Gilbert said. “People who suffer real tragedy and trauma typically recover more quickly than they expect to and often return to their original level of happiness, or something close to it. That’s the good news – we are a hardy species, even though we don’t know this about ourselves.”

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3