A rise of murders is traumatising inmates and staff, and making life harder for staff. But even in prison, violence isn’t inevitable

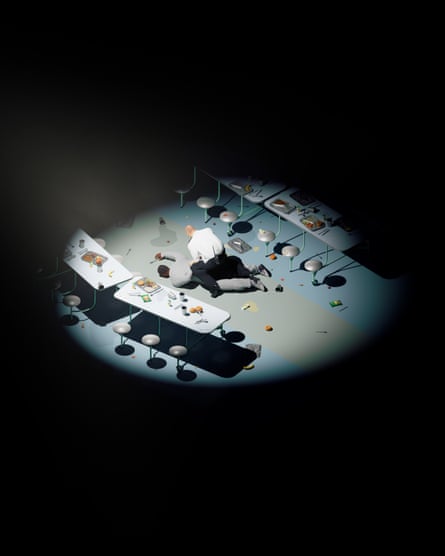

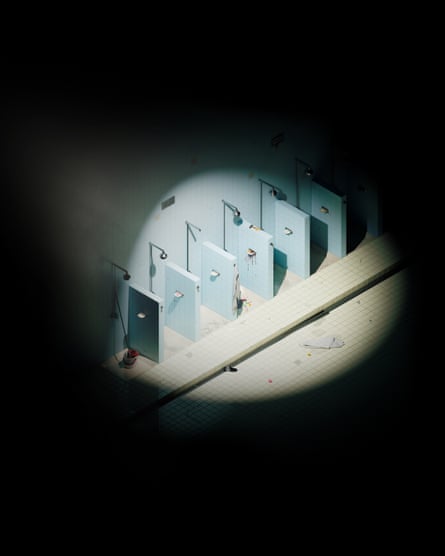

There are hotspots for violence in prison. The exercise yard, the showers. There are peak times, too. Mealtimes and association periods are particularly volatile.

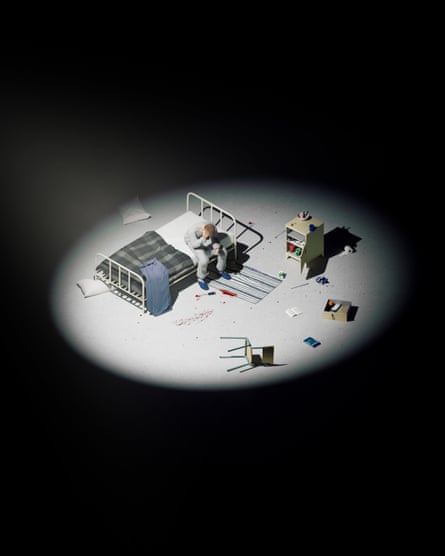

But first thing in the morning is not when you expect to hear an alarm bell. I certainly didn’t, at 6am in my office on the residential wing of a high-security prison in late 2018. All prisoners were locked up at that time. But overcrowding has long been a problem in UK prisons, and keeping three men in cells designed for one can be a recipe for disaster.

When I reached the scene, I found one of my colleagues standing outside a cell with his keys in the lock, poised to open the door. The control panel next to the door showed a blinking orange light. The cell bell can be activated by prisoners inside to call for officer assistance. Normally this would be a request for toilet roll or paracetamol. But that day was different.

Inside the cell, one man sat trembling on the top bunk. Another stood with his back to the window, arms folded, T-shirt spattered with blood. The third prisoner lay prone on the floor. He was conscious, but only just. The eerie stillness of that cell was suddenly broken by noise and urgency. The officer beside me radioed for an ambulance. The dedicated search team was deployed to photograph the cell and preserve available evidence. Staff from the segregation unit were assigned the unenviable task of relocating the perpetrator to a “dry cell” (one with no toilet, sink or furniture) where he would not be able to scrub the dried blood – the evidence – from his skin or his T-shirt. Later, in the dry cell, he would proceed to smash the light fitting, and use the shards of plastic to assault the next officer who opened the door.

The prisoner we had found unconscious on the floor, a man in his 60s serving a short sentence for burglary, was taken to hospital. He spent several days in a medically induced coma. The liquid I’d noticed streaming from his nose was, in fact, brain fluid. One of the doctors who treated him likened his injuries to those he would expect to see after a high-speed road traffic accident. Mercifully, he survived. His assailant was subsequently assessed as high risk, and will never share a cell again. He was already serving a life sentence, so additional charges were deemed not to be in the public interest. Yet the impact of his actions was far-reaching. For the victim, obviously, who was lucky to survive. But also for the man on the top bunk, who in the middle of such appalling violence had the courage to reach out and press the cell bell. And for the staff who responded, for whom such incidents are difficult to forget. We were all acutely aware that if that cell bell hadn’t been pressed, if there hadn’t been enough of us who turned up early to work that morning, the outcome could have been very different.

A year or so later, I was reminded of that morning as I sat for a training session in an auditorium in Manchester. On stage, a slight woman in her 70s was delivering a talk about trauma and men in prison. She spoke about how their lives are often defined by trauma long before they’re incarcerated, how they continue to accumulate trauma during their sentence – and how we all pay the price of it afterwards.

As part of the training day, we were supposed to discuss how often we saw signs of trauma – the results of childhood abuse and neglect – on the landings as prison officers. How did abuse manifest itself on prison wings? Were prisoners able to manage their personal hygiene? Did they interact in a healthy way with others? And we did talk about it, for a bit. I recalled the man in one prison I worked at: he had grown up in a children’s home, and was triggered by the sound of boots outside his cell door. As a 12-year-old, he’d come to recognise the sound of a certain pair of boots, scuffed heels, the way they dragged along the linoleum at night. Then paused outside his bedroom door.

But there is something about these kinds of conferences that always feels a little condescending, as if frontline prison staff could not have worked out the impact that child abuse can have on a person without a psychologist explaining it. Something a little pointless, too. When are we supposed to see signs of this stuff? Prisoners are banged up for up to 22 hours a day in some places. And if we do see it, what next?

I was sitting at a table with people who wore the same uniform I did. Lightweight jacket, cheap zipper that kept breaking, Queen’s crest. Heavy black boots. Starched white shirt. Dubious expressions.

Our nametags set us apart from one another.

Chloe, HMP Berwyn

Reece, HMP/YOI Feltham

Neil, HMP Full Sutton

And me: Alex, HMP Belmarsh

I’d been in the Prison Service for a while by then. Enough to know something about most other prisons in England and Wales.

Berwyn: new officers out of their depth. Problems with staff corruption. A relatively new prison, staffed by inexperienced officers and running a limited regime, with little time outside cells. A senior officer from there once told me she’d had to explain to a new officer why it was inappropriate to pluck a prisoner’s eyebrows for him.

Feltham: like a mini war zone. Young men from different areas, different gangs, a tangled web of rivalries and affiliations that only intensified behind bars. Education is compulsory in young offender institutes – or at least it’s supposed to be – but the time it took to get prisoners into their classrooms often surpassed the time allocated for learning. Staggering a regime in this way, meaning that multiple small groups of people are moved to education or activities at different times to avoid them coming into contact, is typical of prisons with high rates of violence. But it also means that mistakes are inevitably made. It is near-impossible to keep up with the ever-changing feuds and allegiances between groups, to remember who is friends with who, and who has links to which area.

Full Sutton: an officer had been taken hostage there back in 2013. Back then, I was a junior officer still on probation. Even now, I can remember how that incident affected us all in the highest security prisons. The knowledge that if it could happen there, it could happen anywhere. And that feeling that hung in the air over the next few days as we unlocked the cells. I held my keys differently. Checked my angles differently.

That day in 2019, at the training session in Manchester, Full Sutton was back in the news. A convicted paedophile serving 22 life sentences had been murdered there a few weeks earlier.

“Were you on shift?” I asked Neil.

He stirred his weak coffee, black granules spreading like oil.

“I was on scene,” he said.

All prison officers have witnessed violence. It’s a part of the job. But I was floored by the level of depravity that Neil had dealt with in that cell. The fact that it had happened in a place such as HMP Full Sutton made it all the more shocking. Full Sutton is a high-security, category A prison. It benefits from higher staff-to-prisoner ratios, more thorough security procedures and additional resources. Category A prisons tend to be smaller. They are more conducive to a community environment, where prisoners and officers often call each other by their first names. Where workshops and classrooms have full attendance. Where governors are a visible presence, regularly seen visiting the residential wings, the segregation unit, the healthcare department. Better funded. Better resourced. Or at least, that was how things were in the not-so-distant past.

Prisoner-on-prisoner murders were rare when I joined the Prison Service in 2012. There were incidents that came close, but the courage and quick thinking of officers had led to near-misses rather than deaths. Back then, it would be news if an officer was assaulted. Times have changed. Now, there are regular stories of violence, corruption, overcrowding and suicide in prisons. Between April 2013 and March 2016, there were 13 murders in prisons in England and Wales. I had hoped never to work in a jail when one took place, but I had no such luck.

I’d transferred out of one prison only weeks before a young man was stabbed to death on the residential wing where I had been based. I’d listened as one of my former colleagues described watching the paramedics carry out open heart surgery on the landing; his stunned disbelief that the thing we’d all said was “only a matter of time” had actually happened. The panic and intensity, and then sudden disorientating stillness: a young man stabbed to death in a filthy cell.

I considered myself lucky that I’d left that prison before the murder took place. But then I was on shift when a murder was committed at the next jail I worked. On shift – but not on scene. Responding to an incident is not the same as being the first one there. It’s not the same as being the one to find the victim, or to intervene while that kind of violence is happening right in front of you. I was grateful that I hadn’t been that officer. But even as paramedics took over and I walked away, I knew I’d have a hard time forgetting what I’d seen.

In the last few years of my decade as a prison officer, I’d come to better understand how the job was affecting me. In the grip of a cold February shortly after the murder, I’d been inside my office when the red light above the door started flashing. The looping alarm bell followed seconds later. And then a panicked shout for staff. It took me seconds to reach the cell and seconds more to glance inside. Inside, a man’s body was slumped against the toilet. It was too late. Not a murder or a suicide. A drugs overdose. He had been a quiet man, occasionally picked on by the younger prisoners. He never caused staff any problems.

Hours later, I was pulling my lightweight jacket tighter around my body as I stood on a doorstep in Croydon, the chaplain beside me. The rain fell in a fine mist underneath the streetlights. Christmas lights were still sparkling in one window. The woman who was listed as the prisoner’s next of kin opened the door. When we told her the news, she did not react the way I’d expected. Her tears were not of grief, but a mixture of relief and bitterness. She had spent so many years of her life afraid, she said. The quiet man who had never caused any problems had been abusive and violent. He had smashed her windows and chased her with a baseball bat. She felt some semblance of freedom only when he was locked up, and yet she had lived in constant fear that he’d get back out. I forgot his face after a few months, but I have never forgotten hers.

Nor did I ever forget the lifer whose hand I’d held on the operating table. Sporadic chest pain, suspected to be a panic attack, had turned out to be serious heart disease. I was 23 and he was 25. His expression when he asked me if he’d be OK. My voice as I said, “Yes, of course.” Because I thought that he would be OK. I thought that he was too young to die, and the operation was safe and the hospital world-class, and I thought I was saying the right thing. But he never woke up.

All of this had done what you might expect it would. It made me a little more cynical, a bit paranoid about personal safety. But my experiences in prisons had done something else, too. I empathised a little more with the men I locked up. I could see that none of this was black and white, as I had once thought. I felt conflicted about the men I met who had done terrible things but were not always terrible people, and I felt conflicted about the others whose offences I struggled to look past. I was conscious of the pain they had caused, and yet I could recognise that the scaffolding of their lives was flimsy. The places where they should have been helped, they were not.

I saw a version of that in my own experience. This system, of which I had once been so proud to be a part, now showed me contempt. I resented being at that Manchester conference in my cheap uniform, learning things that were blindingly obvious, being told what I needed to do by people who would never have to do it, and the painful knowledge that none of this would ever translate to life in prison as I knew it. Because how could it? When would any of this happen? And who would do it?

That night in Manchester, we ate in a gastropub not far from the city centre. I sat beside Chloe from HMP Berwyn. We’d met before a few years earlier, on our hostage negotiators course. She was bright, funny, with bleached blond hair and a stud in her nose. We laughed about that course and the incidents we’d faced: the time a prisoner sprayed a fire extinguisher in her face, the time a teenager with hepatitis B spat in mine. In both cases, a better system might have provided some kind of support for the officers afterwards, but nothing was forthcoming.

It’s hard for the prison officers trained as peer supporters to support their peers when jails are understaffed. If there aren’t enough officers to relieve the peer supporters, and there aren’t enough officers to relieve the ones who need peer support, what happens next? Not much, is the answer. There’s the employee assistance helpline, where the person on the other end has no knowledge of prisons or the specifics of that environment. Or the teams of skilled wellbeing personnel, who supposedly respond to critical incidents in prison within two hours. They sound amazing, but in 10 years of frontline prison work including riots, murders and countless suicides, I never met them. I don’t know anyone who has. In 2024, it was reported that officers today are assaulted nearly hourly. These wonderful-sounding teams might just as well move in.

In the past few years, there have been prisoner murders in the cells at HMP Wormwood Scrubs, HMP Belmarsh, HMP Fosse Way, HMP/YOI Stoke Heath, murders in a bunkbed at HMP Bristol, in the showers at HMP Nottingham, the corridor at HMP Coldingley, the gym at HMP Whitemoor, the exercise yard at HMP Woodhill, the landings at HMP Pentonville.

I believed in the system. But now I see it turned inside out. Prisons don’t just hold people who have committed unspeakable violence, they now perpetuate it. Assaults on staff are commonplace. Drones deliver flick-knives to cell windows. Officers are equipped with Tasers to protect themselves and others. A man on remand for terrorist charges escapes. A convicted sex offender is “released in error”.

With 262 releases in error in one year, does anyone really believe the debacle of convicted sex offender Hadush Kebatu’s mistaken release last October was solely down to “human error”? Or the one after that at HMP Wandsworth? Does anyone believe that these are individual mistakes? Because it seems glaringly obvious that these are systemic problems that require systemic changes.

A new checklist isn’t going to cut it. David Lammy, the justice secretary, has described the implementation of new measures as being “the strongest release checks … ever”. I wish that that was all it took to fix our prison system. Some more checks. But the gap between words, reality and decisive action continues to widen.

In 2024, an inquiry was launched by the House of Lords justice and home affairs committee into prison culture and staffing. The inquiry found that prison governor visibility is crucial to effective leadership, that staff and prisoners must routinely see and interact with senior management. The government agreed. And yet we are pressing ahead with plans to build enormous prisons with capacities of more than 1,000, where visibility will be practically impossible.

In the same report, the justice and home affairs committee stressed the importance of purposeful activity such as education, describing it as “essential to prisoners’ personal development and to the reduction of reoffending upon release”. The government agreed. And yet in September, plans were announced to cut spending in education in prisons in England and Wales by up to 50%.

The report also discussed the need to ensure frontline prison staff go through a robust recruitment process and can access high-quality, in-person training to ensure they have the skills needed for such a complex, challenging role. But the recruitment process remains predominantly online, as does much of the training. Starting salaries are between £33,000 and £44,000. Unsurprisingly, retention rates are low and there have been high-profile allegations of staff corruption.

Labour tells us it inherited a Prison Service in crisis – and it did. But 50% cuts to education? Recruiting prison officers over Zoom? Insisting that prison officers are properly supported when every single one wearing that cheap uniform will tell you different? The whole thing exhausts and angers and saddens me. I feel relief and bitterness. Relief I’m out of it. Bitterness that I felt I had no choice. Why on earth would I have stayed?

Late last year, two more murders – both at HMP Wakefield, in the space of less than a month. That brought last year’s total to eight. Many will see the death of these particular men as no great loss to society. One of the men had murdered his partner’s two-year-old daughter; the other man was jailed for numerous sex offences, including the attempted rape of a baby. Yet the fact that these murders in prison can happen – and happen regularly – is a sign of something that has gone very wrong.

A murder in prison is not a single event that occurs and then is over. It reverberates. Within the prisons, it is felt in the doctor’s surgeries, classrooms, football pitches, gyms, laundries, cells. The staff feel it – that very specific feeling, that the thing that will happen here one day has happened. The people on shift, on scene, are left with the memories. Boots running, heavy breathing, keys fumbling in locks, alarms looping and red lights on the walls flashing. Paramedics, defibrillators, a white sheet. The coroner’s van comes, silent in the early hours of the morning. So many lives are fractured.

But there are ways back. Violence is not inevitable. I have known two men, one serving a sentence for the attempted murder of the other, who sat in the chapel with staff watching from the sides and talked. It was a difficult, angry conversation, but a necessary one, that allowed them to come to an agreement. They were in one of the best jails in this country, with a decent gym and eight hours out of their cells a day. Neither wanted to serve their time anywhere else. So they agreed to coexist. And to this day, they continue to live on the same wing and play football on the same team.

There are very few good jails these days. Eight hours out of cell a day sounds fantastical now. The cost is immense. Time out of the cells is so important. Learning how to debate, to argue, that back and forth. And education, too, can be transformative. The chatter and buzz of a full classroom in prison. Certificates pinned to the wall. Flowers crafted from toilet roll. Intricate sculptures of skylines and scenery made from matchsticks. In my memory I can see the portraits that one man on the second floor landing would do, his cell dark and smoky, his paintings like looking into another world.

Some names have been changed

4 hours ago

5

4 hours ago

5