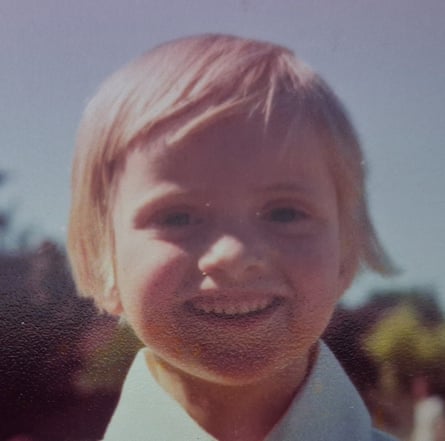

When Leigh White remembers her brother Ryan, she thinks of a boy of extraordinary ability who “won five scholarships at 11” including a coveted place at Bancroft’s, a private school in London. He was, she said, “super bright, witty, personable, generous and kind”.

Ryan killed himself on 12 May 2024. A report written after his death acknowledged significant shortcomings in the support he received while seeking help for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Like many people the Guardian spoke to, he followed the “right to choose” pathway, whereby patients can pick a private provider anywhere in the country for assessment, diagnosis and initial treatment. They then ask their GP to enter a shared-care agreement for prescriptions and monitoring. However, Ryan struggled to get the two services to link up.

The problem lies in the fact that shared care is voluntary and not all GPs agree to it. Some patients told the Guardian their doctor had rejected their private diagnosis on the grounds that it did not meet their standards. This was even after the NHS had paid for it – and despite there being no official rules for private providers to follow. Some, like Ryan, end up stuck in administrative limbo.

Ryan experienced tragedies that affected his mental health. His father and a sister died when he was young and, in 2019, he found his mother dead, a loss from which Leigh said “he never recovered”.

He was treated for bipolar disorder but it became apparent to Ryan that he had been misdiagnosed. Seeking clarity, he was referred by his GP for an ADHD assessment with Psychiatry UK, a private provider, in September 2022. It took five months for him to be assessed and diagnosed, but because of his bipolar history a community mental health review was needed before medication could begin. “Nobody chased anything, or took responsibility,” Leigh said.

In June 2023, Ryan’s housing situation became unstable, triggering acute distress and rapid decline. He was deregistered by his GP practice after he expressed frustration at the delay in getting him help. He sent messages to Psychiatry UK explaining he did not know where to turn, one of which went unanswered.

By early 2024, Ryan was still without a GP, and was exhausted, isolated and increasingly unwell. On 18 June 2024, a Psychiatry UK staff member messaged Ryan to say his medication would be changed to allow treatment to begin sooner. Further messages followed, even though Ryan had died on 12 May. Psychiatry UK did not learn of his death until months later.

“Ryan tried so hard to get help. He was brilliant, but he was left to fall through every crack. He deserved so much better,” Leigh said. “He was fighting a system that demands stability from people who are already in crisis.”

Ryan is one of many people who have been failed by the right to choose system. Psychologists and psychiatrists who spoke to the Guardian shared their concerns that allowing NHS patients to obtain ADHD assessments at private providers was “premature” and had led to a “wild west”.

Right to choose was introduced for mental healthcare and neurodevelopmental care in 2018, in part to ease pressure on waiting lists that were up to a decade long.

But Marios Adamou, a consultant psychiatrist and founder of the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN), said this had come too soon, because “there was no standard in what good assessment looks like and there’s still no standard for what a qualified assessor would look like”.

Right to choose was “poorly regulated, poorly managed and some people are making lots of money out of it”, Adamou said, adding: “If you don’t have regulation for that you are inviting a wild west.”

Experts argue that the problems are partly the fault of assessment guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) being vague. Although some clinics now use quality assessment standards written by UKAAN, there is no national framework for the qualifications required to diagnose ADHD.

Adamou urged the NHS to halt “uncontrolled” spending through right to choose and “divert the money through NHS pathways with specific quality standards”.

Dr Jaime Craig, chief of the Association of Clinical Psychologists, said he regularly heard “concerns about the qualifications of the people completing the assessments and the rigour of neurodevelopmental assessment” under right to choose.

Craig said clinicians should have “the necessary skills and competence to complete a comprehensive assessment which can take into account and assess for possible differential diagnoses and coexisting conditions”.

One clinician revealed that a patient who had come for an autism assessment actually had a visual impairment. Another patient seeking an ADHD assessment had language processing difficulties. Both had risked being medicated for a condition they did not have and missing out on the interventions they needed, Craig said.

“Greater clarity on the required training and regulation of those who can be considered ‘appropriately qualified healthcare professionals’ would help increase public confidence in the rigour of neurodevelopment assessments,” Craig said.

Andrew Jay, director at North East ADHD, said there was pressure from the NHS to drive down prices, leading private providers “to offer a very basic level of care” and putting “pressure on clinicians to be brief and write reports which might not reflect the depth of assessment carried out”.

Adamou noted that he had seen “aggressive promotion” from private providers, including sharing legal letter templates to GPs warning that the patient would sue unless they were allowed to pursue right to choose.

He said ADHD had become “commoditised”, leading unhelpfully to “a new stigma that if you say you have ADHD you’re faking it”. This had been compounded by a failure to triage properly, which he feared was resulting in many people with ADHD being unable to secure a diagnosis – and much-needed treatment.

A report by Psychiatry UK into Ryan’s case concluded that staff should be encouraged to ask medical secretaries to check that requests to GPs were followed up, and that consultant psychiatrists should contact a patient’s community mental health team for advice and referrals.

Dr Joanne Farrow, medical director at Psychiatry UK, apologised for any part it “played in Ryan not getting the help he needed from local services” and said she was saddened to hear of his death.

She said Psychiatry UK had invested in better quality and safety infrastructure, had evaluated policies and processes and opened a contact centre to provide faster responses to patients. She added: “Our investigation highlighted the need for better communication with GPs and mental health providers to ensure our patients receive the best care possible.”

Danielle Henry, director of policy at the Independent Healthcare Providers Network (IHPN), said that private providers now deliver more than half of all NHS-funded ADHD assessments.

“Patients and their families should be reassured that as with NHS providers, there is clear oversight of the sector, with our members being regulated by the Care Quality Commission, as well as adhering to clinical guidelines including from Nice, UKAAN and the ADHD Assessment Quality Assurance Standard for Children and Teenagers (CAAQAS),” she said.

“Giving NHS patients the right to choose their provider for ADHD assessments and diagnoses has resulted in much needed new capacity and innovation being brought to the NHS, the contribution of which has been critical in helping the health service meet growing patient demand in this area,” she added, noting that problems around “shared care” should be addressed urgently.

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3