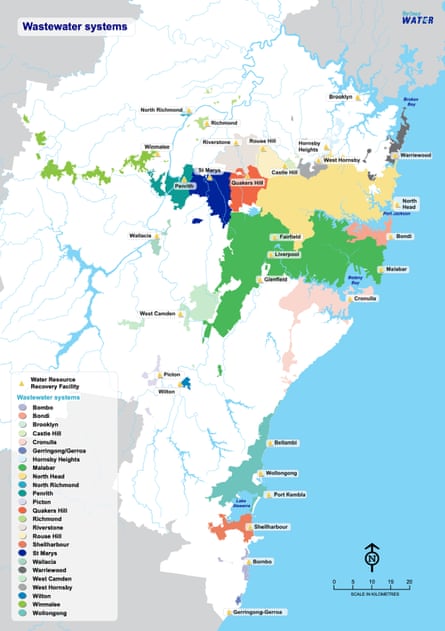

A giant fatberg, potentially the size of four Sydney buses, within Sydney Water’s Malabar deepwater ocean sewer has been identified as the likely source of the debris balls that washed up on Sydney beaches a year ago.

Sydney Water isn’t sure exactly how big the fatberg is because it can’t easily access where it has accumulated.

Fixing the problem would require shutting down the outfall – which reaches 2.3km offshore – for maintenance and diverting sewage to “cliff face discharge”, which would close Sydney’s beaches “for months”, a secret report obtained by Guardian Australia states.

This has “never been done” and is “no longer considered an acceptable approach”, the report acknowledges.

Sydney Water’s deepwater ocean outfalls (Doof) assessment report, dated 30 August 2025, was produced for the New South Wales Environment Protection Authority, which has been investigating the “debris balls” that closed numerous beaches in late 2024 and early 2025.

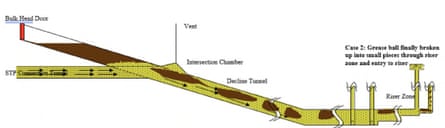

“The working hypothesis is FOG [fats, oils and grease] accumulation in an inaccessible dead zone between the Malabar bulkhead door and the decline tunnel has potentially led to sloughing events, releasing debris balls,” the report concludes.

“This chamber was not designed for routine maintenance and can only be accessed by taking the Doof offline and diverting effluent to the cliff-face for an extended period (months), which would close Sydney beaches.”

The report states the first poo balls to wash up on Coogee beach on 15 October 2024 were likely caused by a loss of power at the plant, which stopped “raw sewage pumping” (RSP) for four minutes. The subsequent “rapid increase to high flow again” could have dislodged part of the fatberg accumulated behind the bulkhead door.

A similar drop and then increase in pressure, this time “due to wet weather”, occurred on 11 January 2025.

“This rapid change in instantaneous flow could also have given rise to the debris ball landings in January 2025,” the report states.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

The report notes “this area is large enough to hold a sufficient quantity of FOG that could generate the debris ball landings in October 2024 and January 2025”.

Sydney Water initially denied its sewerage system was responsible, stating in November 2024 that “there have been no issues with the normal operations of the Bondi or Malabar wastewater treatment plants”.

“Sydney Water acknowledges the tar balls may have absorbed wastewater discharge, which was already present in the water while forming, however, they did not form as a result of our wastewater discharges,” a spokesperson said at the time.

The EPA admitted in November last year – after Guardian Australia reported on a separate secret oceanographic modelling study – that evidence “collected by Sydney Water … narrowed the origin of the debris to within the Malabar system”. The Malabar outfall started operating in 1990.

The latest report reveals “Sydney Water’s working hypothesis is that a significant amount of FOG has accumulated in the intersection chamber between the Doof bulkhead stopboards and the ocean outfall tunnel over time”.

The bulkhead door is usually under water, and can only be opened at low tide and during low flows in the system. The report states it is impossible to safely go beyond the stopboards. The huge fatberg is thought to be in a 300 cubic metre chamber beyond the stopboards.

Sydney Water is now regularly cleaning the accessible part, which is “an extremely risky operation”. In April 2025, it removed 53 tonnes of accumulated FOG, including debris balls, the report states.

“This material had not consolidated into a large single mass such as that seen in sewer networks and commonly referred to as ‘fatbergs’ but rather could be broken up.” But, the report notes, “an accumulation of FOG in this area is possible”.

The cause of the debris balls was likely that “FOG had accumulated on the landward side of the intersection chamber and that this build up had been captured in a quiescent zone”.

Then, “the sudden drop in flow followed by the sudden increase in flow drew this material into the main flow path and pushed it through the Doof exiting from one or more risers, diffusers and nozzles”.

Unlike most cities, Sydney only does primary treatment of its sewage – straining out the solids. Elsewhere, secondary treatment uses settlement tanks and disinfection techniques before releasing the wastewater or recycling it.

Singapore, for example, treats its sewage to such a high level that it can be reused in the drinking water system.

The August report reveals that FOG in the Malabar wastewater system have risen by 39% over the past 10 years. Volatile organic compounds – including cleaning products, cosmetics, paint, fuels and other chemicals – have risen by 125%.

“The current best thinking is that concentrations are so high in the system that there has been a significant increase in accumulation and that FOG is now escaping wherever possible, often in wet weather events through hydraulic relief structures in the network and less frequently from the deep ocean outfall,” the report states.

Fatbergs have caused problems in other cities – but in different ways.

In London in 2017, a fatberg weighing the same as 11 double-decker buses and stretching the length of two football pitches was found to be blocking a section of London’s ageing sewage network.

The congealed mass of fat, wet wipes and nappies took three weeks to remove.

New York City spends about $19m a year removing fatbergs from its sewers and is running a campaign “trash it, don’t flush it”.

Sydney Water’s options to deal with its potentially huge fatberg are limited. The corporation told the EPA it plans to continue cleaning the part of the bulkhead it can access, while devising campaigns to try to dissuade Sydneysiders from putting FOG down the drain.

It also plans to initiate a trade waste program for food businesses. It estimates that 12,000 food businesses could be operating without any waste approvals, and many of these are feeding into the Malabar system.

“We are reviewing operational and maintenance practices, including regular inspections of accessible areas, and strengthening fats, oils and grease management through ongoing cleanouts, trade waste customer engagement, source control reviews, and community education on proper disposal practices,” a Sydney Water spokesperson says.

“The EPA has advised that all Sydney Water facilities involved were operating in compliance with their environment licences during the events. Any regulatory outcomes, including potential penalties, are determined independently by the EPA.”

The state water minister, Rose Jackson, announced on Friday – after Guardian Australia asked questions about the findings of the secret August report on Thursday – a “Malabar system investment program estimated at $3bn over the next 10 years”.

“[It] will reduce the volume of wastewater that needs to be treated and discharged via the Malabar deep ocean outfall,” Jackson said in a statement.

But some say it’s time for a fundamental shift in thinking.

“The outfalls are old school technology, and our sewerage system needs to

be modernised,” the Total Environment Centre’s Jeff Angel says.

“This should mean a higher level of treatment, but also and importantly, much more recycling, so there is less being dumped into the ocean and to conserve our water resources.”

Guardian Australia reported 12 months ago that Sydney Water planned to spend about $32bn to improve the city’s sewerage system over the next 15 years, but waste would continue to be pumped into the ocean off its famous beaches.

A spokesperson for the EPA said this week it was working closely with Sydney Water to establish a program for the removal of built-up fats, oils and grease from the bulkhead area at Malabar.

“As part of Sydney Water’s environment protection licence review, we are considering this build-up in consultation with the wastewater expert panel,” they said. “We expect to finalise licence variations by mid-February.”

1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2