Like his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, which won the Booker prize in 2017, George Saunders’s new novel is a ghost story. In Vigil, an oil tycoon who spent a lifetime covering up the scientific evidence for climate change is visited on his deathbed by a host of spirits, who force him to grapple with his legacy. What draws Saunders to ghost stories? “If I had us talking here in a story and I allowed a ghost in from the 1940s, I might be more interested in it. It might be because they are in fact here,” he says, gesturing to the hotel lobby around us. “Or even if it’s not ghosts, we both have memories of people we love who have passed. They are here, in a neurologically very active way.” A ghost story can feel more “truthful”, he adds: “If you were really trying to tell the truth about this moment, would you so confidently narrow it to just today?”

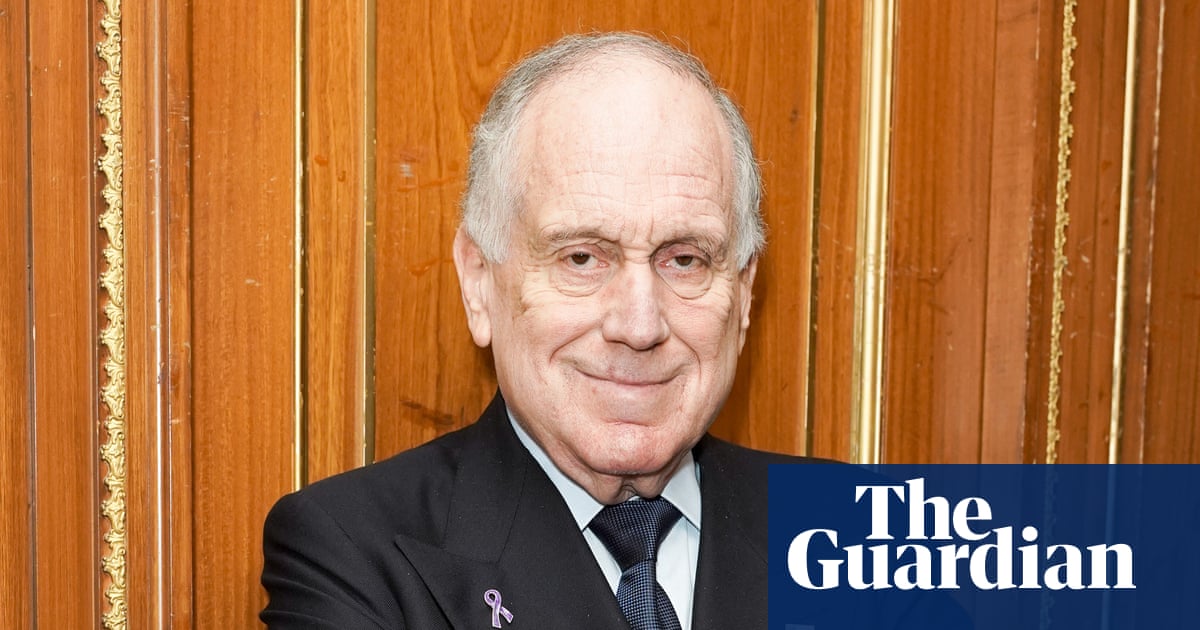

Ghosts also invite us to confront our mortality and, in so doing, force a new perspective on life: what remains once you strip away the meaningless, day-to-day distractions in which we tend to lose ourselves? “Death, to me, has always been a hot topic,” Saunders says. “It’s so unbelievable that it will happen to us, too. And I suppose as you get older it becomes more …” he puts on a goofy voice: “interesting”. He is 67, grizzled and avuncular, surprisingly softly spoken for a writer who talks so loudly – and with such freewheeling, wisecracking energy – on the page. He says death is close to becoming a “preoccupation” for him and he worries that he is not prepared for it.

About 25 years ago, Saunders was on a passenger plane that was hit by geese shortly after taking off from Chicago. There was a loud bang, the plane began making terrible noises, black smoke filled the cabin, people screamed, the lights of the city appeared to approach very fast, and Saunders believed he was going to die. At the time he was “at peak spirituality”, a Tibetan Buddhist who meditated for three hours a day, and yet he experienced pure terror. “It was like all the elements of my identity got rolled back. I wasn’t thinking about writing. I wasn’t even able to think about my family, there was just some primal self that was about to be lost,” he recalls.

“And then this funny, I don’t know …” he trails off for a moment, apparently unsure if funny is the right word, before telling me that the teenage boy next to him asked: “Sir, is this supposed to be happening?” and he, his fatherly instinct kicking in, replied with bravado: “Yes, of course”. It is a funny story – Saunders puts on voices to tell it – and he deploys it the way he uses humour in his fiction, to temper the earnestness and moral seriousness of what he is trying to convey.

The plane landed safely in Chicago, and for about a week after, Saunders felt euphoric. Buddhists believe that a true awareness of one’s own mortality enables a person to fully embrace the wonder of being alive. “It’s almost like if you were invited to a really wonderful party and it was going to end at 11.30 and they let you know that – it would change the quality, as opposed to: this is a six-day party, or an infinite party,” he says. He has had “flare-ups” of that feeling since, and he chases it in his writing.

Saunders won a MacArthur genius grant in 2006 and is perhaps best known for his short stories. He has published five collections and a couple of novellas, which are dark and satirical, often set in fantastical, dystopian worlds – strange theme parks or malls or futuristic prisons – that present American society through a fun-house mirror, its most grotesque and absurd and spirit-crushing features magnified. They are compassionate stories, told by a man whose advice to students – a 2013 commencement speech on regretting “failures of kindness”, a mid-pandemic letter on the importance of bearing witness – often seems to go viral, and who sees writing as a “sacramental act”. He holds the impassioned, optimistic belief that literature can make us better people, because it requires that both the writer and reader transcend themselves and their coarser instincts, and exercise their capacity for reflection and empathy. Just as when he meditates he might practise a visualisation to generate compassion – one involves imagining someone you love dearly being washed away down a river, and as that feeling of wanting to help wells up you try to expand the feeling outward, to all people – he has found the act of writing enables him to expand his empathy outwards. It pushes him to what he describes as “a certain view of things in which everyone is just me on a different day, or a different life”.

The ghosts in Lincoln in the Bardo and Vigil can practise empathy in the most direct, literal way, by stepping into each other’s minds. Vigil is told from the perspective of Jill Blaine, the ghost of a sweet-natured, 22-year-old newlywed who was killed in a car bomb explosion and then entered the mind of her killer. Her moral purpose is to comfort the dying, and she calls her guiding philosophy “elevation”, the view that our lives, all our failures and our triumphs, were inevitable, shaped by forces beyond our control. “Who else could you have been but exactly who you are?” she asks KJ Boone, the oil tycoon. “All your life you believed yourself to be making choices, but what looked like choices were so severely delimited in advance by the mind, body, and disposition thrust upon you that the whole game amounted to a sort of lavish jailing.” Is she right? Saunders says he hasn’t decided, and believes good fiction should aim to ask the right questions, rather than provide answers. “My job is to be the rollercoaster designer and try to set the elements up so it produces the maximum amount of ‘wow’… My feeling is always to err on the side of ‘what makes sparks fly’, and then the meaning is kind of secondary.”

But Saunders does remember being six or seven years old and thinking, when someone told him “oh, you’re such a good boy”, that “I didn’t choose any of those things, that’s just the way I am”. He recalls when he was younger still, three or four, knocking over a coffee pot and scalding his sister, and later worrying about whether he had done it on purpose. He’s always been “neurotic” and “OCD” (although not officially diagnosed), and refers to these looping, self-interrogating thoughts as his “monkey mind”. Writing is a “mental health thing” for him. It quietens the monkey mind.

He grew up in Oak Forest, south Chicago, where his father worked for a coal company and later owned and ran a fried-chicken franchise called Chicken Unlimited. He was an “errant” reader, who read the books his father left for him before he went to work, an eclectic mix that included Machiavelli’s The Prince and The Other America, an exposé of American poverty by the socialist writer Michael Harrington. He got into Colorado School of Mines to study geophysical engineering and read in his spare time, but had “no taste”. “Ayn Rand was the only novelist I really liked for a while and I didn’t detect anything false in it. Because I was so young I thought: ‘Well, that’s how it is,’” he says.

After college he worked with an oil exploration crew in Sumatra, and wrote fiction in his spare time, trying to emulate Hemingway. “If you had seen the stuff I was writing at 25, you would never think that person would be published. You would feel sorry for them,” he says. He was, in his telling, redeemed by an unearned arrogance. “I think this is true and it is even a compositional principle: if you say ‘I’m going to do this’, and then you don’t allow yourself to be rebuffed by the things that should rebuff you, then eventually the problem heals,” he says.

A few years after returning from Asia, when he was living a “nicely out-of-control life” in Texas, he wrote a story unlike anything he’d written before, inspired by a dream he’d had about a theme park without any gravity. A Lack of Order in the Floating Object Room was published by the Northwest Review, and it helped him win a funded MFA at Syracuse University in upstate New York. He spent his first weeks in Syracuse sleeping in a truck.

There, he met a novelist named Paula Redick, and he fell in love so quickly and completely that in three weeks they were engaged and less than a year later they were married. They have two daughters, now grown, and live together in LA with their 13-year-old dog, Guin. “It’s such a nice life,” he says, with real feeling. He and Paula write in their separate offices and meet up for lunch, they walk the dog, they are each other’s first readers – although she is a better one than he is. He knows that if a story doesn’t produce a strong emotional reaction in her, it’s not ready. They push each other to produce work with spiritual weight. “It’s not enough to be clever or sarcastic, we want there to be that undercurrent of something deeper,” he says.

How did he know so quickly that she was the one? “The word that comes to mind is undeniable: I cannot not get on that boat,” he says. She was “very deep”. Both had been raised in religious families – he was a “really rabid Catholic kid”, she was from a “kind of fundamentalist” family – and they remained very “spiritual”. “We have that at our core: like, are we at all moving towards being better people and more ready for the end?” Plus, Paula was “so beautiful”, he adds. Zadie Smith once joked to him that, in old photos, George – very blonde and hirsute, with a mullet and a moustache – looks as if he is abducting Paula.

Paula got pregnant and went into labour at four months, forcing her to go on bedrest to save the baby, and Saunders completed his degree by correspondence. His thesis was “crap”, he says, because he laboured under the misconception that he needed to produce Serious Literature, and reverted to writing lifeless, derivative prose. On graduating, he got a job as a tech writer. He noodled about on boring work calls, composing scatological poems accompanied by little doodles, and it cheered him that they made Paula laugh. Eventually, he began writing short stories again. This time, he made them funny. In 1996 he published his first short story collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline. A year later, he began teaching at Syracuse, where he remains a creative writing professor. “I often think at that level the difference between very, very good writing and great writing has to do with letting something into the mix that you’ve been holding back for complicated reasons.” For him, it was humour.

Saunders is an enthusiastic teacher. Since 2021 he has been running his Story Club Substack, which he posts bi-weekly, to discuss craft. “I thought I’d do it for a year, and then it turned out to be so much fun,” he says. It now has more than 315,000 subscribers and about 30,000 paying ones. “There’s something really non-internet-y about the comments. People are so smart and generous,” he says, which he finds a “consolation”, a corrective to the political climate. Sometimes he finds himself wondering: “how does this impulse to kindness coexist with, say, ICE raids?”

I had run into Saunders on the stairwell on the way to the interview, and somehow by the time we reached the second floor landing we were discussing our shared fears over Trump’s authoritarianism. “I keep thinking, ‘well, the people won’t tolerate this’, but people are tolerating it,” he says now. Mostly he feels “yucky” when talking about such things, however. “The person I am at a family party arguing politics is not so interesting, just another old dude with opinions,” he says, aware that many of his views are “robotic”, a product of his media diet. When writing fiction, he’s a different creature politically, one forced to consider multiple perspectives. “That person, through working every day, can become a slightly more interesting person, and that person is a little slower to judge, a little more confused, a little quieter,” he says. “That in itself made me think I don’t have to be so despairing about, say, the partisan political war, because we’re all just trapped in that lower mode. There is this possibility, however remote, that we could for brief periods ascend out into the other mind – and then it’s actually not so terrifying. Now, the problem is scale. I mean, if just one person does it, we’re still fucked.”

He began writing Vigil because he was curious about whether the people who devoted decades to covering up climate change had regrets now, “given the weather”. The challenge – and he sees it as a moral one – is to “see if you can imagine how this action, which to you seems so bad, can to that person seem good”, he says. It’s partly a question of technical skill. “There’s a facile way to do it and a complex way to do it, and you can only find that out in the lines themselves,” he says. “If you don’t do it right, it leads to a facile kind of sympathy, that kind of liberal thing where someone drives a spike through your head and you say ‘thank you for the coat rack’.” In other words, he didn’t want to present KJ Boone in a sympathetic light or suggest his actions were right – but he did want to make him understandable, recognisably human and complex, the qualities we often struggle to recognise in our adversaries in the heat of a political argument.

Saunders is still pondering how, given his platform, he should talk about politics when he goes on tour with Vigil in February. “To preach to the converted in the familiar terms in which they’re preached to feels a little too good, like it’s too much sugar. Whereas my nature is to be a little more of a peacemaker. But that’s dangerous right now because I don’t want to be a peacemaker for this regime,” he says.

For now, he has a few months of quiet, walking the dog, pondering potential new writing projects. “The one thing I’m doubling down on is: just keep making fictive worlds. Improve the quality of your thought, improve the quality of your compassion, by that sacramental exercise, then whatever you have to do you’ll be better equipped,” he says. And then, inevitably, he adds the joke: “also start weightlifting, build a machine-gun turret …”

3 hours ago

6

3 hours ago

6